The Subversive Art of Poetry

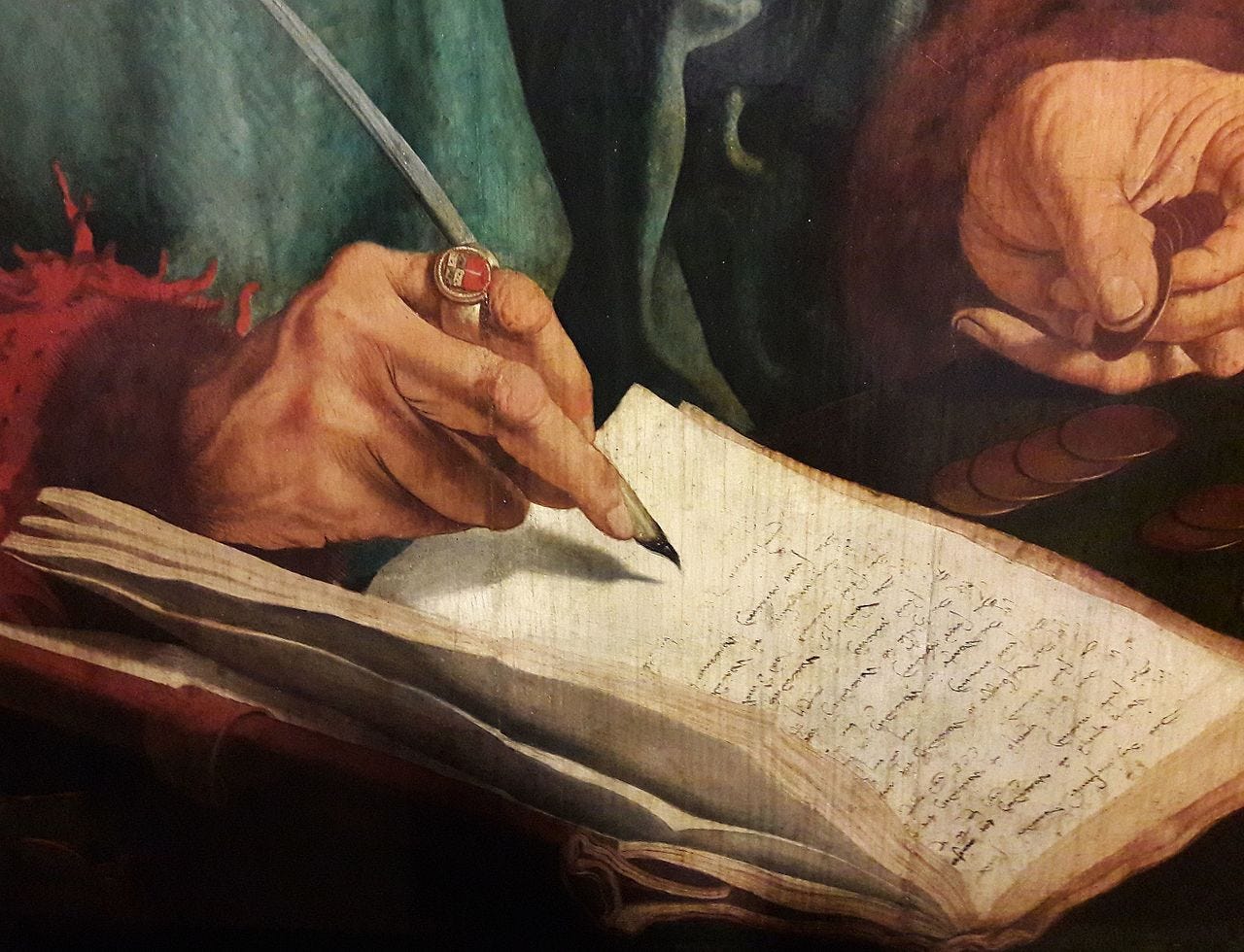

To memorize a Shakespearean sonnet or a passage from Dante is to resist the erosion of memory, to store within oneself a treasury of language and meaning that no algorithm can retrieve on command.

Poetry, often seen as a refined arrangement of words meant to distill human emotion or experience, has long been more than an artful expression. It has been a force of subversion. From whispered verses of political dissent to the rhythmic outcries against oppression, poetry has persistently challenged the status quo, giving voice to the silenced and unsettling the comfortable.

Yet in the modern world, the subversive power of poetry takes on a different form. No longer merely a tool of political resistance, it now wages war against a subtler, more pervasive threat: the erosion of memory, the flattening of expression, the mechanization of language. Poetry is an insurgency against the automated and the ephemeral, a defiance of distraction and passivity.

To read poetry, to memorize it, to speak it aloud, and ultimately to write it—each of these acts asserts intellectual and emotional sovereignty in a world that seeks to render language sterile and thought mechanical. Poetry resists reduction; it cannot be neatly summarized, algorithmically distilled, or consumed in passing. It demands attention, engagement, and presence. In this way, it remains one of the last strongholds of the deeply personal.

To memorize a Shakespearean sonnet or a passage from Dante is to resist the erosion of memory, to store within oneself a treasury of language and meaning.

Midway along the journey of our life I woke to find myself in a dark wood, For I had wandered off from the straight path.

This deliberate act of internalizing verse emerges as an insurgency. It is a refusal to capitulate to the age of the transient, an assertion of cognitive discipline against the anesthetizing drift of passive consumption. Yet, recitation—speaking aloud that which has been internalized—is where the real sedition lies. Against the background hum of artificial voices and talking heads, the spoken poem reclaims the orality of civilization. One’s own voice, shaping the meter and breath of verse, upends the mechanized assault of digitized language, reasserting the primacy of human cadence over the sterile monotone of algorithmic speech.

Yes, the reciter of poetry wages a battle against linguistic decay, wielding phonemes like insurgent weapons to reclaim the richness of spoken language. Consider:

Hope is the thing with feathers That perches in the soul, And sings the tune without the words, And never stops at all;

With every measured modulation of voice, every deliberate enjambment, every well-timed pause before the volta, the speaker disrupts the clipped, mechanical rhythm of modern communication. Poetry restores the natural harmonics of language, giving breath and body to words that might otherwise be reduced to mere data points in an indifferent system.

But deeper still lies analysis, another act of disruption, another subversion of the digital mindset. To analyze poetry is to defy the impulse to skim, to flatten, to extract only the quotable, the digestible, the monetizable. Great poetry demands a kind of attention that our fragmented, attention-economy minds are no longer engineered to give. To parse a Shakespearean sonnet, to unlock the cryptic allegories of Dante’s Inferno, is to resurrect the nearly extinct practice of deep reading, of sustained intellectual engagement unfettered by the clickbait urgencies of the now.

The structure of a Petrarchan sonnet, the calculated hesitations of a Dickinsonian dash, the caesura in a line of Chaucer—these do not yield to the blunt instruments of sentiment analysis. They demand patience, curiosity, interpretative nuance, all the faculties that the digital age strives to render obsolete. The mere act of reading poetry closely, of tracing its allusions, feeling its meter in the bones, understanding its layered significances, amounts to an intellectual insurrection against the passive consumption of content.

And what of writing poetry—or, better yet, composing it? Here perhaps the subversion reaches its zenith. To write poetry, to craft an original line with both beauty and meaning in mind, is a radical defiance of the artificial and commonplace. It requires the poet to wrestle with language at its most elemental, to bend and chisel syntax into shape, to invoke muses that the machines cannot summon. I have witnessed this myself as a teacher: When students, having read, memorized, and recited the great works, turn to crafting their own verse, they engage in one of the most beautiful and intellectually rewarding pursuits available to the mind. No longer mere receivers of poetic tradition, they also become its active participants, shaping language with the same care and precision as those who came before them. Consider this sonnet (“Ode to the Noble Cow”), written by one of my former 16-year-old English Literature students after weeks of studying Shakespeare’s sonnets:

O steadfast beast that feeds both man and land, With golden milk and beef so richly prime, Your gentle lowing marks the course of time, A rural song both humble and grand. Through pastures green, in herds you proudly stand, Your cud-chewed wisdom wholly more sublime Than leaders crafting laws both dense and grim— Oh, were they half as useful to this land! Yet I, poor wretch, without a cow to keep, Must sip my milk from cartons, cold and thin, And dream of days beside a bovine friend. No sturdy hooves to wake me from my sleep, No soulful eyes to gaze with love within— Alas! My life’s deprived of such an end.

To write poetry is to step into the centuries-old conversation of human experience, to find one’s own voice amid the echoes of Shakespeare, Dante, and Dickinson. It is the act of transforming thought into melody, observation into imagery, emotion into rhythm. The budding poet must grapple with words until they yield something genuine: a metaphor that illuminates, a turn of phrase that surprises, a cadence that lingers in the mind like music.

No! This is not mere arrangement; it is discovery. It is the imagination at play, the intellect at work, the heart in motion. Each new poem is an original constellation of meaning, brought forth with all the weight and wonder of human consciousness. It teaches patience and the slow unfolding of thought. To write poetry is to develop an intimacy with language, to perceive its hidden harmonies, to nurture the ability to express what so often remains unspoken.

Finally, to stand before an audience, whether in a poorly-lit classroom or a sun-drenched lecture hall, and recite one’s own poetry is to commit the ultimate act of literary subversion. It is to reject the passivity of the digital spectacle, to defy the paradigm of text as mere content, to insist on poetry as an embodied, communal act.

It is to reclaim presence and to affirm the weight of a living voice. In that moment, the poet does more than share words; he creates an encounter, drawing both speaker and listener into a space where meaning is not scrolled past but felt, where attention is not fragmented but fully given. Poetry in performance refuses to be merely archived or consumed in passing; it lives in the breath, in the cadence of spoken word, in the electric exchange between voice and ear. Against the backdrop of distraction and depersonalization, it insists that language is not just a tool for communication but a force that binds, animates, and endures.

So, yes, poetry stands as an unyielding bulwark against the digital degradation of memory, language, and imagination. It is a subversion of the passive. It is a rebellion against the automated. It is a defiance of the disposable. It is an insurgent force against the forgetting machine.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Very good analysis. Indeed, poetry is subversive and always has been.

I think it’s especially so today because of how it works in contrast to the workings of modern life.

Today’s world is reductive and systematic. From job descriptions to daily routines, Pinterest inspos and productivity hacks, every aspect of our lives focuses on definitions, certainty, processes, and the illusion of control.

Poetry works differently at every level. It is a language of relationships, intuition, lived experience and emotional depth. And indeed there will always be a place for it because there are so many life situations for which definitions and analysis leave us wanting. Poetry integrates us with our experiences and with the world; today’s values separate, isolate, and throw our lives into abstraction through technology and digital experiences. In such an environment, the former kind of activity is inherently subversive.

It is a rebellion against the automated. It is a defiance of the disposable...... AH YES !....