The Subversive Art of Slow Reading

What was once an act of immersion has now become an exercise in evasion. There’s no time to linger or to contemplate because the screen is perpetually pushing us forward.

By now, we have all become so comfortable with our fractured attention spans, with our fingers hovering over a screen—scrolling, swiping, double-tapping—that we’ve forgotten what it feels like to truly read. Not skim. Not scan. Not fall victim to the F-pattern. We float across texts in broken arcs, grazing bolded headers, skipping over entire paragraphs, convinced that we’ve absorbed the information simply because we can pull it back up at any given time. But this is not reading. This is an experience of consumption, not of engagement. It’s been a kind of cognitive massacre.

What was once an act of immersion has now become an exercise in evasion. There’s no time to linger, to contemplate, to return to the page for a second time, because the screen is perpetually pushing us forward. It's as if we’re all chasing a fleeting, invisible deadline—a deadline that makes its presence known only by the ping of a notification, the pop-up ad, or the blinking cursor that threatens to evaporate our thoughts altogether.

But there is an alternative, a kind of rebellion against this increasingly shallow existence. This rebellion goes by many names—slow reading, deep reading, thoughtful reading—but it can best be understood as a reclaiming of a practice now deemed almost radical. We live in a world that demands we “keep up,” that nudges us to “stay current,” that tempts us with disposable tidbits of content that we can consume with all the efficiency of a junkie at a buffet. It is a world driven by the promise of access, a world that insists that more is always better and that faster is always necessary.

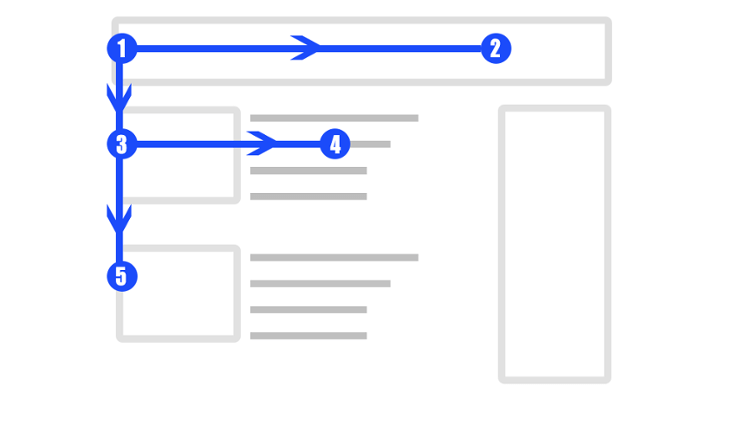

The F-Pattern of Reading

Enter the F-pattern. A structure driven by the tyrannical demands of the digital age. It’s a curse, a way of reading forged in the desperate hope that if we just consume enough content, we might find meaning somewhere in the fractured pieces. This is what has been dubbed The F: When we read on screens, our eyes dart across the page in jagged, erratic arcs. We never settle; we never sink deep enough into the text to allow it to settle in us. Instead, we hit the headlines, the bullet points, the bolded morsels, the hashtags. We move from snippet to snippet, our brains trained to only follow the highlights, to gloss over anything that doesn't shout. We are like shoppers in a chaotic marketplace, never slowing down long enough to hear the nuances, to sense the subtext.

What we are left with is a kind of cognitive dissonance, a permanent low-grade hum of anxiety that comes from trying to be everywhere at once, to take in all things without ever truly processing any one thing. The F-pattern is not merely a symptom of the digital age; it is its heartbeat, its pulse. And it is running us ragged.

Fortunately, there exists another rhythm: one of deep, deliberate engagement. In contrast to the F-pattern, slow reading is a deliberate, immersive process. It asks for more from us than just our eyes skimming across the surface. It demands our full attention, our undivided focus. It’s not about speed; it’s about presence. It’s about being in the text, not just getting through it. It is a form of reading that rejects the tyranny of efficiency, the idea that time is only valuable if it’s maximized. Instead, slow reading acknowledges that time spent in focus, in reflection, in the careful unpacking of meaning, has a kind of intrinsic value. This is the kind of reading that allows us to feel the weight of a sentence, to savor the texture of words, to return to a passage and find something new each time. It is an invitation to be fully present in the act of reading.

For educators in classical schools, slow reading is not just a pedagogical strategy; it is a core tenet of the classical tradition itself. Even in a world that overvalues efficiency and instant gratification, classical educators should understand the value of deliberate, focused engagement with texts. Classical education emphasizes deep reading of primary sources, where students are encouraged to sit with a text, to wrestle with it, to analyze it not just for surface-level facts but for its deeper meanings. Here, slow reading isn’t a mere suggestion; it is the method of instruction.

Modeling Slow Reading

In the classroom, educators can foster slow reading by first modeling it. Teachers should read aloud, slowly and thoughtfully, drawing attention to the layers of meaning in each sentence, each phrase. They should pause after key passages, allowing students to reflect on what has been said, to ask questions, to re-read and discover new insights. This process of modeling patience in reading teaches students to slow down, to savor the text rather than rush through it. Teachers can also introduce practices such as Socratic seminars or intentional discussions, where students are encouraged to dive deeply into a text, considering its implications, challenging assumptions, and considering alternative interpretations.

The Art of Annotation

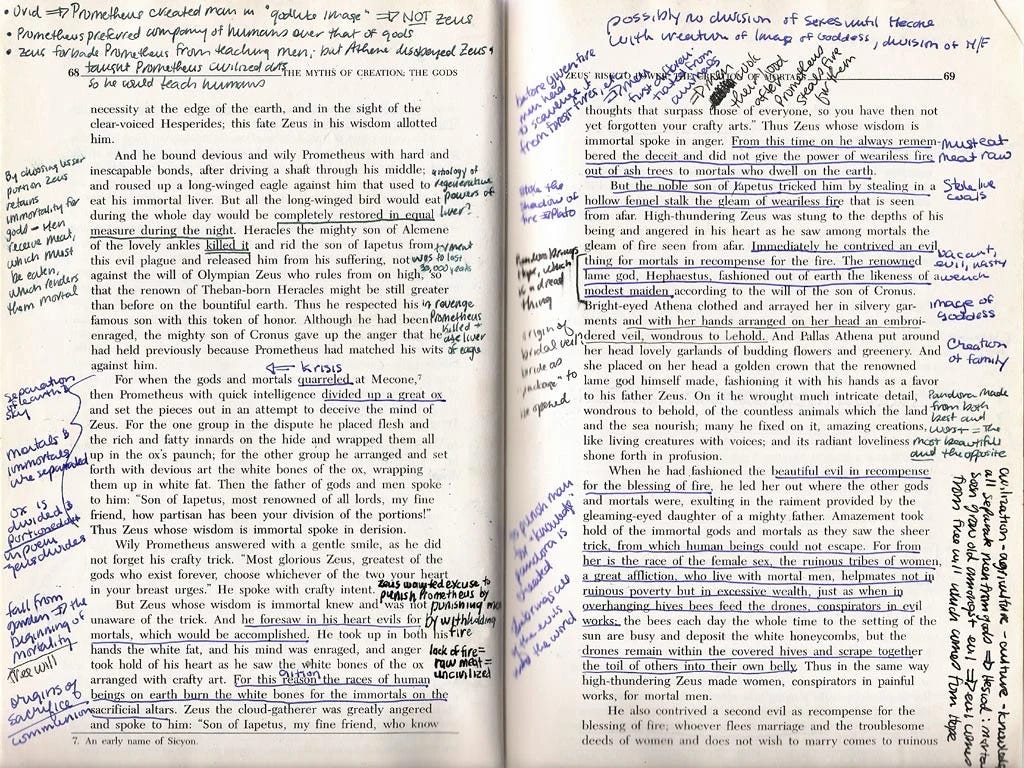

Another key practice is the integration of annotation into the slow reading process. When students engage with texts through annotation, underlining key passages, writing notes in the margins, and asking questions, they actively participate in the reading. This creates a dialogue with the text, a conversation that slows down the process and forces students to engage with the material rather than passively absorb it. (I will address this art more fully in a future article.)

The Proper Environment for Reading

Finally, slow reading requires an environment conducive to reflection. In a classroom that is filled with distractions—where screens are constantly pinging and notifications are flashing—deep reading is impossible. Teachers can help mitigate this by fostering a space of quiet and focus. Whether through physical space, the removal of digital distractions, or the deliberate scheduling of time for reading, educators can create a sanctuary where students are free to immerse themselves fully in the text.

The irony is that the technology designed to give us endless access to information has simultaneously deprived us of the one thing we most need to truly engage with that information: time. And so, the solution is almost absurdly simple: slow down. To read with intention. To read not just to extract facts or glean insights but to engage deeply with the text, to allow it to affect us, to challenge us, and to push us into deeper thought. This is reading that demands patience, that resists the call of instant gratification. It is reading that invites us to immerse ourselves in the language of the text, not just to glance at it.

To be frank, slow reading is a rebellion. It is a rebellion not against the world itself, but against the mindless urgency it imposes. In slow reading, we make space for something richer, more meaningful—a space that technology, despite all its promises, can never give us.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

I majored in philosophy because I was only able to read slowly. Now I choose to read slowly. Few things in life make me feel better than an hour of slow, calm, reading of a great text.

Enjoyed this piece Michael. I wholeheartedly concur. Slow reading has changed my life for the better. I look forward to more of your essays.

There are quite a few slow reading groups on Substack. I am leading a year-long journey through Homer's works, and Simon Haisell has been leading groups through classic books for several years now.