The Subversive Art of Active Reading

To read actively is an act of defiance, of self-discipline, of engagement with something larger than oneself. It is to think, to wrestle, to question, and, ultimately, to grow.

Somewhere between the casual skimming of a news feed and the solemn engagement of a scholar with a sacred text lies the Art of Active Reading. It is not merely the act of decoding words but of wrestling with meaning, of engaging in a silent yet vigorous dialogue with the writer. Yes, the act of reading—true reading—demands a reinvigoration of spirit. No longer can we afford the posture of the passive reader-as-receiver, eyes gliding over text. No, the reader of substance must be of another breed: engaged, alert, primed for intellectual combat.

The reader of substance must be of another breed: engaged, alert, primed for intellectual combat.

You may already know this, but the ability to read actively—to absorb, question, and respond to a text—has become an endangered skill. What follows is an argument for reclaiming that skill, for cultivating the habits of the active reader who approaches a book not as a passive recipient but as a participant in an intellectual pursuit.

The Preliminaries: Before the Battle is Joined

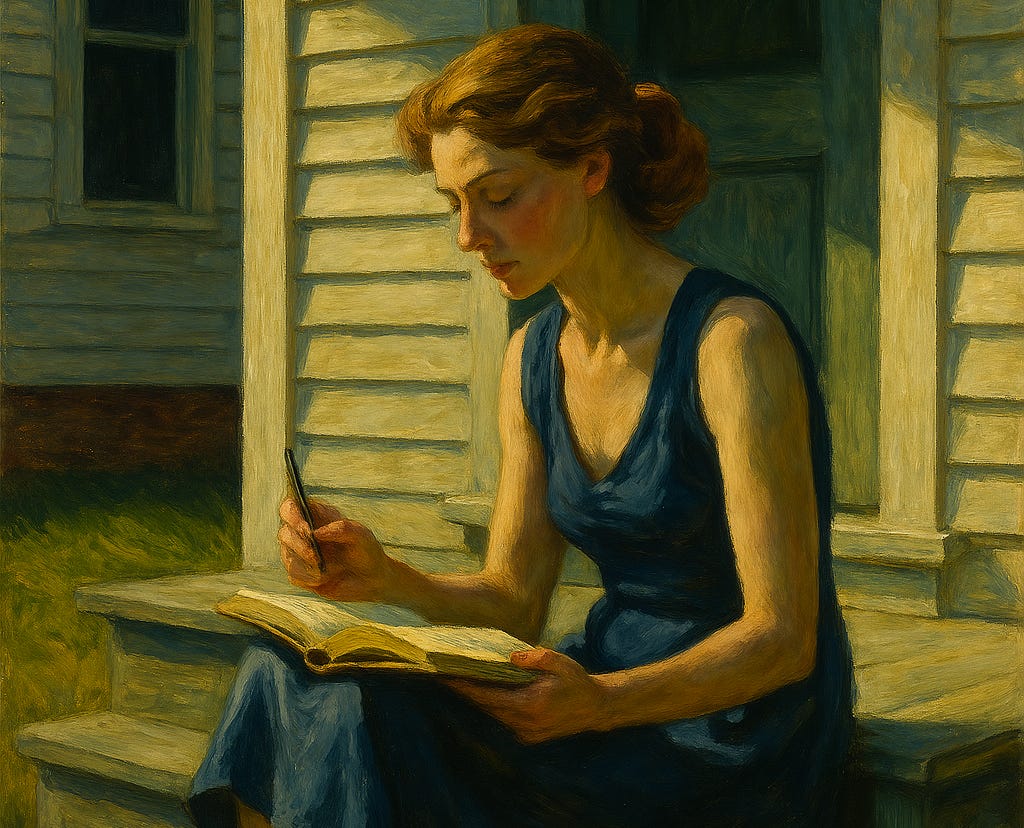

One does not wander into a text unarmed. The active reader outfits himself much as a mountaineer before an arduous ascent—pen or pencil in hand (sword or staff, depending on disposition), a dictionary within reach (the trusty map, lest one lose his way), and, most crucially, a seat that disciplines rather than seduces, a chair where focus may sharpen to a point.

Survey the terrain before the journey begins: skim the contours of the text, identify its shape, its mood, its density. Find the signposts: the author’s name, the time of writing, the ideological baggage smuggled within the prose. To read blindly is to be led blindfolded through unfamiliar streets, bumping against meaning without ever truly beholding it.

Engaging the Text: A Dialogue, Not a Dictation

A passive reader is a whisper in a crowded room, drowned out by the surrounding din. The active reader, on the other hand, is a street preacher arguing with the void, defacing the margins with underlines, circles, and exclamations—every annotation a stake driven into the heart of textual ambiguity. The great sin of reading without a pen is that it permits thought to evaporate, to dissipate into the ether before it has even fully formed. To annotate is to make the text one’s own, to lay claim to its meaning through engagement, through struggle, through interrogation.

Do not merely underline but summarize. Do not merely summarize but question. Do not merely question but argue. What did the author mean? Why did she phrase it this way? What remains unsaid? What contradictions bubble beneath the surface? What in this text aligns with your own experience, and where does it veer into the alien, the unfamiliar? If it does not provoke—if it does not force you to shift in your seat—then perhaps you have not yet truly read it. Hmm.

The Aftermath: Processing the Spoils

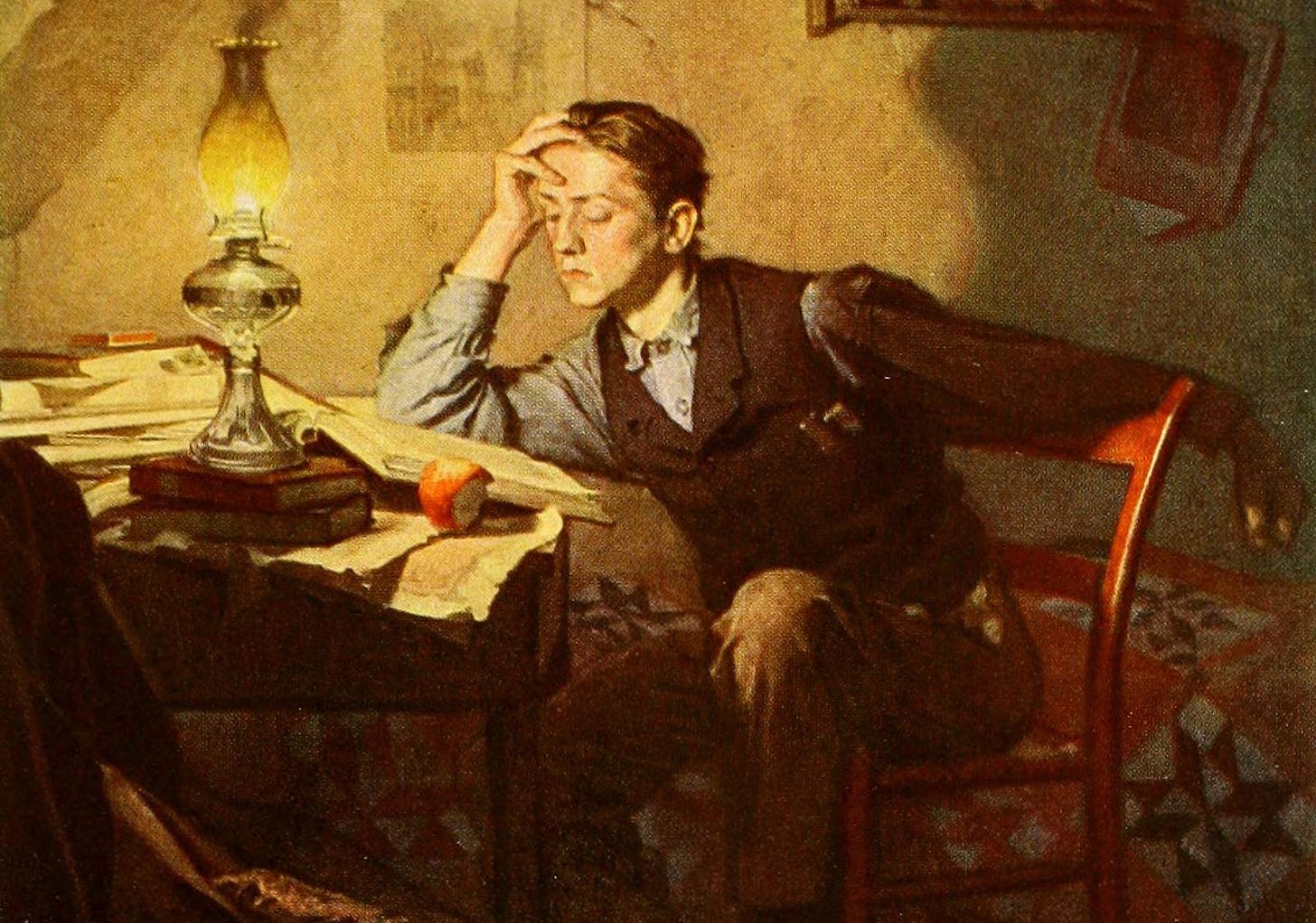

The novice may assume the act of reading concludes when the final period is reached, the last word consumed. But the seasoned reader knows that the real work begins in the aftermath. A book closed too soon is a meal half-digested, its nutrients left untapped. Reread. Reannotate. Outline, condense, extract. Let the text percolate in conversation, its themes and motifs surfacing at unexpected moments. Allow its ideas to haunt your thoughts, to revisit you in idle moments, to challenge your convictions when you least expect it.

A book closed too soon is a meal half-digested, its nutrients left untapped.

To discuss a text is to extend its life, to rescue it from the silence of its final page. Do not let it languish. Summarize it to another, even if only in muttered phrases as you walk. Reduce it to its essence, its skeleton, its architecture. What remains? What was smoke and what was steel? What is worth remembering, and what deserves to be discarded? The lazy reader finds himself forever treading water, grasping at words that slip through his fingers; the active reader builds a raft, a foundation upon which every subsequent text rests, solid, navigable, permanent.

The Mark of the Skilled Reader

The gulf between the competent reader and the struggling one is vast, yet it is not impassable. The skilled reader enters a text with prior knowledge in tow, seeking connections, making predictions, weaving meaning from the disparate threads of prose. He is neither gullible nor cynical, neither accepting nor dismissive, but rather engaged in a ceaseless process of inquiry. He slows when the text demands deliberation, accelerates when the terrain is familiar, and is unafraid to double back when meaning eludes him. He welcomes ambiguity, recognizing in it not an obstacle but an invitation—an invitation to think, to engage, to work.

The struggling reader, on the other hand, is unmoored, cast adrift in a sea of ink, at the mercy of the waves. He reads as one listens to the murmurs of a foreign tongue, catching syllables but never meaning, allowing words to pass through him as though he were no more than a sieve. He stares at dense paragraphs with the same vacant panic of a man before an impenetrable forest, unsure where to begin, hesitant to step forward.

But the path can be learned. The habits of the great readers—those who read with the intensity of a scholar deciphering sacred texts—are not secrets reserved for the elite. They are methods, disciplines, tools forged in the fires of necessity. They are available to all who would wield them. The difference is only in who dares to pick them up.

Toward a Reclamation of Reading

You may have noticed that reading is now little more than an afterthought, an inconvenience, a relic of a slower time. Our eyes, accustomed now to the rapid-fire onslaught of digital content, struggle against the demands of true engagement. We skim, we scroll, we process information not in paragraphs but in fragments, and in doing so, we grow accustomed to shallowness. But it is precisely in this age of distractions that the art of deep reading becomes most necessary.

To read actively is to resist—to resist the pull of passivity, the lure of surface-level understanding, the temptation to let meaning wash over us without soaking in. It is an act of defiance, of self-discipline, of engagement with something larger than oneself. To read actively is not merely to read; it is to think, to wrestle, to question, and, ultimately, to grow.

And so, pen in hand, eyes alert, let us begin again.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Reading is the art of becoming alive

In total agreement. That should light a fire under many readers. “Reading” visual art should be encountered the same way - with its own visual grammar and visual elements of meaningfulness. In a world awash with easy to grab reference images used for backgrounds or to set a “mood”, the inevitable result is that images, sometimes even great ones, become wallpaper. At that point it’s like having a bookcase full of unread books.