The Subversive Art of Annotation

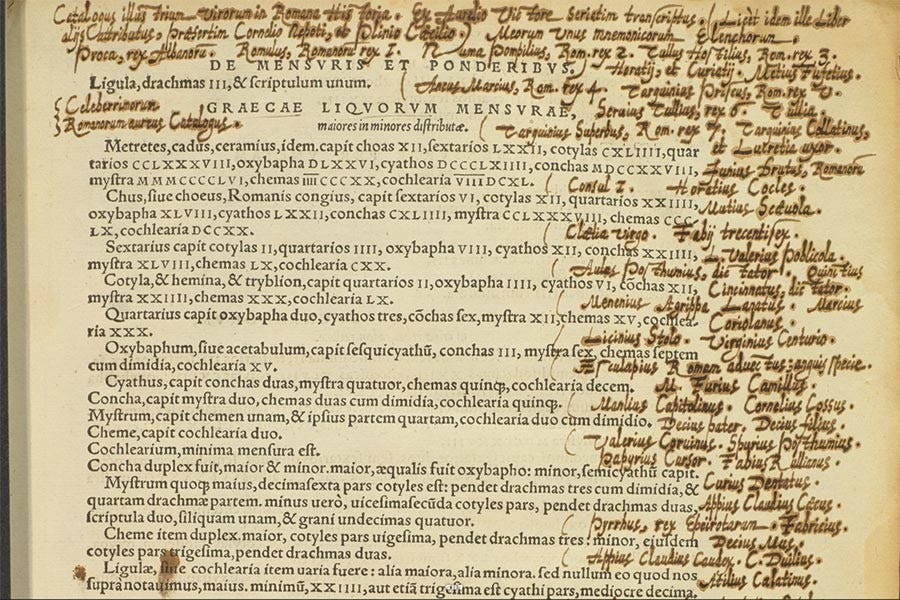

To annotate is to engage in whispered dialogue with the dead. The hand tracing notes in the margin is shaking hands across time, reaching into the past to argue, to marvel, to collaborate.

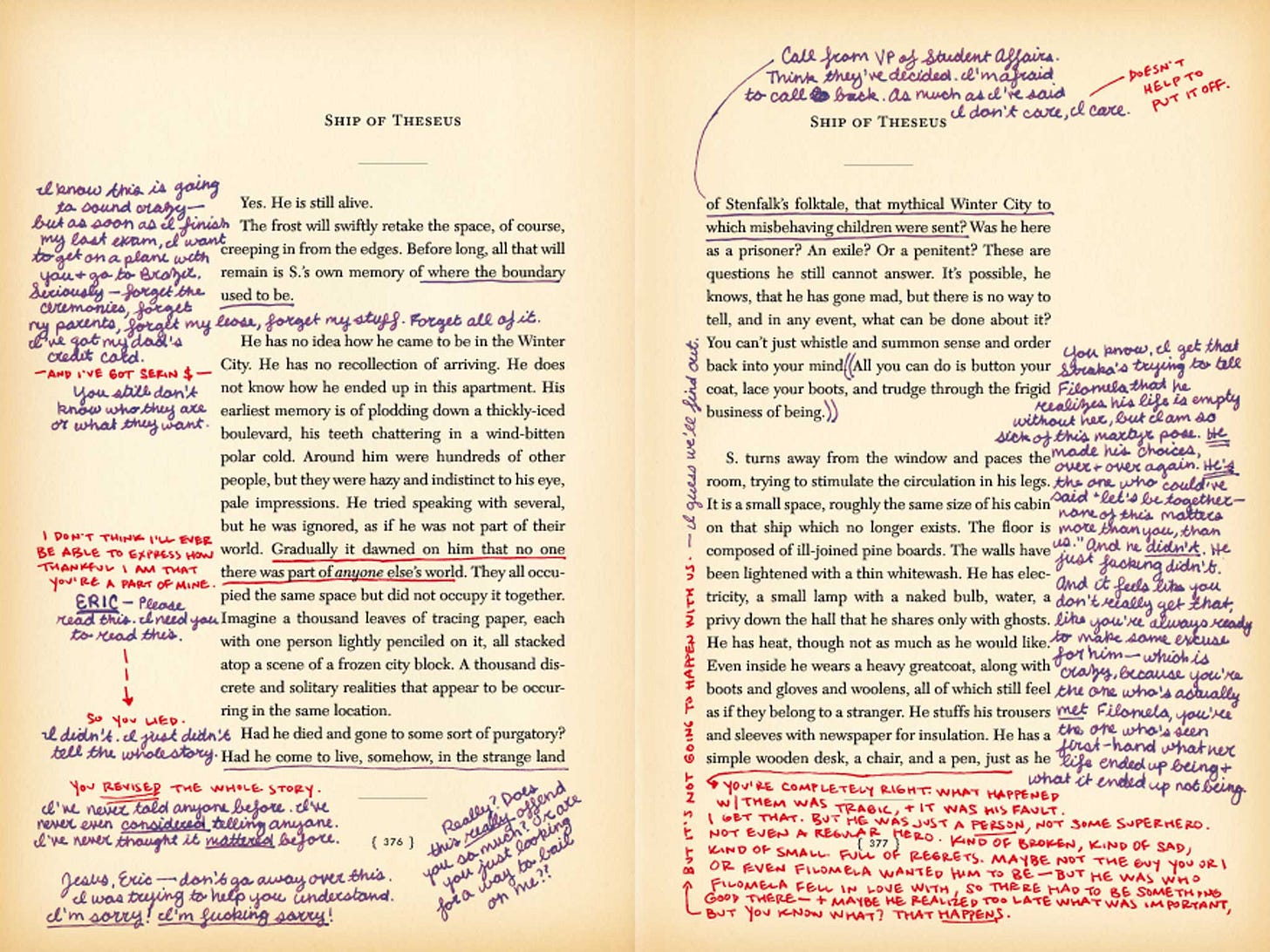

There is, within every reader worth the ink spilled in his direction, an impulse both criminal and holy: to scrawl and to deface the pristine margins of a book with the unruly evidence of thought. We call this annotation, perhaps the most ancient and clandestine of literary subversions, standing as it does at the contested border between passive absorption and active insurrection. It is an act of heresy against the tyranny of the printed word—blasphemous, perhaps, to those who revere the sacred untouchability of a text—but also the very gesture by which a book is rescued from the museum glass of mere consumption and dragged, kicking and screaming, into the flickering present of a mind alive with questions.

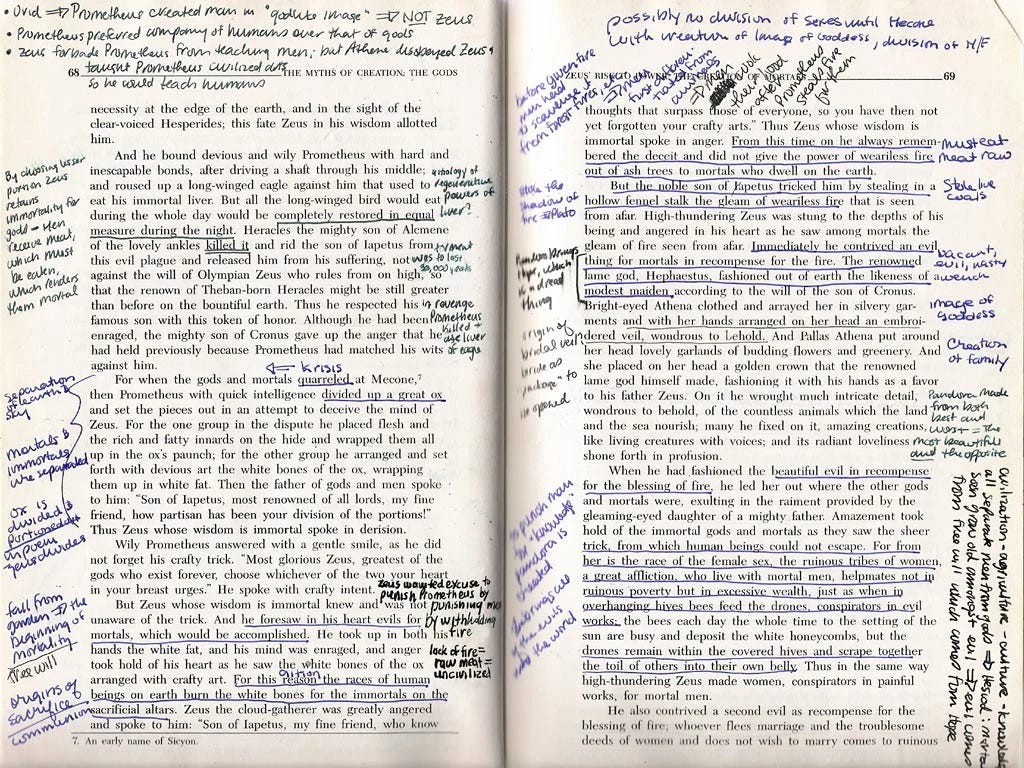

Reading, if one is reading properly, is to think, and thought, unruly thing that it is, resists containment. It overflows and demands articulation. If it is not spoken, it will be written. And so, the margins—those innocent blank expanses to the right and to the left—become battlefields, sites of interrogation, where the reader takes up the pen not as a scribe but as a conspirator. Here, in the tight scrawl of a half-formed argument, in the underlined passage thick with silent agreement, in the snide rebuttal penciled next to an author’s pronouncement, is evidence of that most radical act: the refusal to simply receive. The marked book is the thought-through book, the wrestled-with book, the book taken apart and reconstructed in the mind of its reader.

To annotate is to refuse passivity. The student who highlights but never questions, who transcribes but never argues, is a vessel waiting to be filled, a functionary of memorization rather than a practitioner of thought. The learner, if he is truly learning, does not merely listen; he interrogates. He provokes. He cross-examines the text as if it were a witness under oath. And the book, for its part, must be made to testify. Every sentence, every assertion, is a suspect whose alibi must be checked against the evidence of experience, the record of history, the logic of reason.

And yet, in this seemingly adversarial relationship, there is also intimacy. To annotate is to engage in whispered dialogue with the dead. The hand tracing notes in the margin is shaking hands across time, reaching into the past to argue, to marvel, to collaborate. And the act itself, this primitive scratching of graphite or ink, is no mere abstraction but a kind of muscle memory, a way of inscribing knowledge not just onto the page but into the nervous system. A thing written is a thing retained. Even the motion of the hand, the pressure of pen against paper, summons thought into sharper focus, solidifies what was once vaporous into something concrete, repeatable.

Perhaps this is why annotation has always carried a faint whiff of the transgressive. Monks in candlelit scriptoria, slipping personal asides between lines of scripture; revolutionaries in dimly lit taverns, scrawling rebuttals in the margins of manifestos; students in dull lecture halls, peppering their textbooks with exasperated retorts—each, in his own way, engaging in an act of literary rebellion. To annotate is to claim a book as one’s own, to refuse to be dictated to, to insist upon a place in the ongoing conversation of ideas. It is an act of possession, of transformation, and—above all—of resistance.

Because learning, real learning, has never been a matter of sitting still. It is a violent, disruptive thing, a shaking of foundations, a refusal to accept. The annotated book is not just read; it is lived in, argued with, built upon. It bears the scars of engagement, the marginalia of a mind refusing to be merely filled, insisting instead upon thinking for itself. And in the end, that is the greatest subversion of all.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

I am always thrilled to find a handwritten annotation. Your essay is perfect.

This is another great argument for reading physical books rather than books on devices.