Beauty & the Grammar of Stone - Part II

Like spoken and written language, architecture possesses its own grammar: a set of principles governing the arrangement of its elements, ensuring clarity, coherence, and meaning.

This is the second article in a series on Classical Architecture. A new article in the series will be published each Saturday morning. Read Part I.

To speak of classical architecture is to engage with a structured language, one as precise as mathematics, as expressive as poetry, and as purposeful as any system of communication devised to order human experience. Like spoken and written language, architecture possesses its own grammar: a set of principles governing the arrangement of its elements, ensuring clarity, coherence, and meaning. Just as words form sentences and equations express relationships, architecture employs proportion, symmetry, and ornament to create spaces that not only serve practical needs but also elevate the human spirit.

The classical tradition, developed over millennia, is fundamentally about ordering the elements of the built environment to foster understanding and to shape human experience in a way that is both intelligible and ennobling. Rooted in the pursuit of harmony and intelligibility, classical architecture is governed by five key principles: order, symmetry, proportion, harmony, and ornament. These principles, much like the rules of language or mathematical axioms, form a framework through which architects translate material into meaning, shaping the structures that define our cultural and civic life.

Principle I: Order

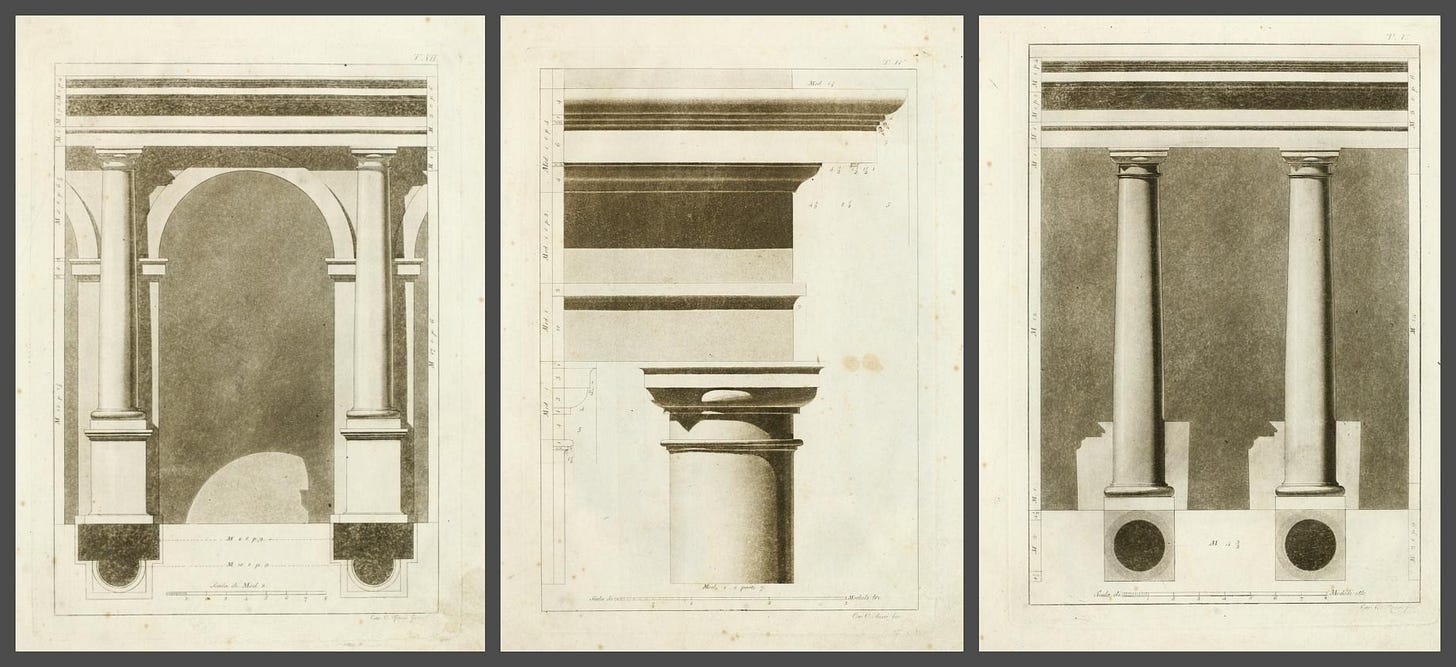

Order, in the architectural sense, is the systematic arrangement of elements according to established rules—an expression of logic and hierarchy that renders the built environment legible. Just as syntax in language dictates the proper sequence of words to convey meaning, architectural order ensures that individual elements relate coherently to one another and to the whole. It is not merely an aesthetic preference but an intellectual framework that transforms raw material into a meaningful composition.

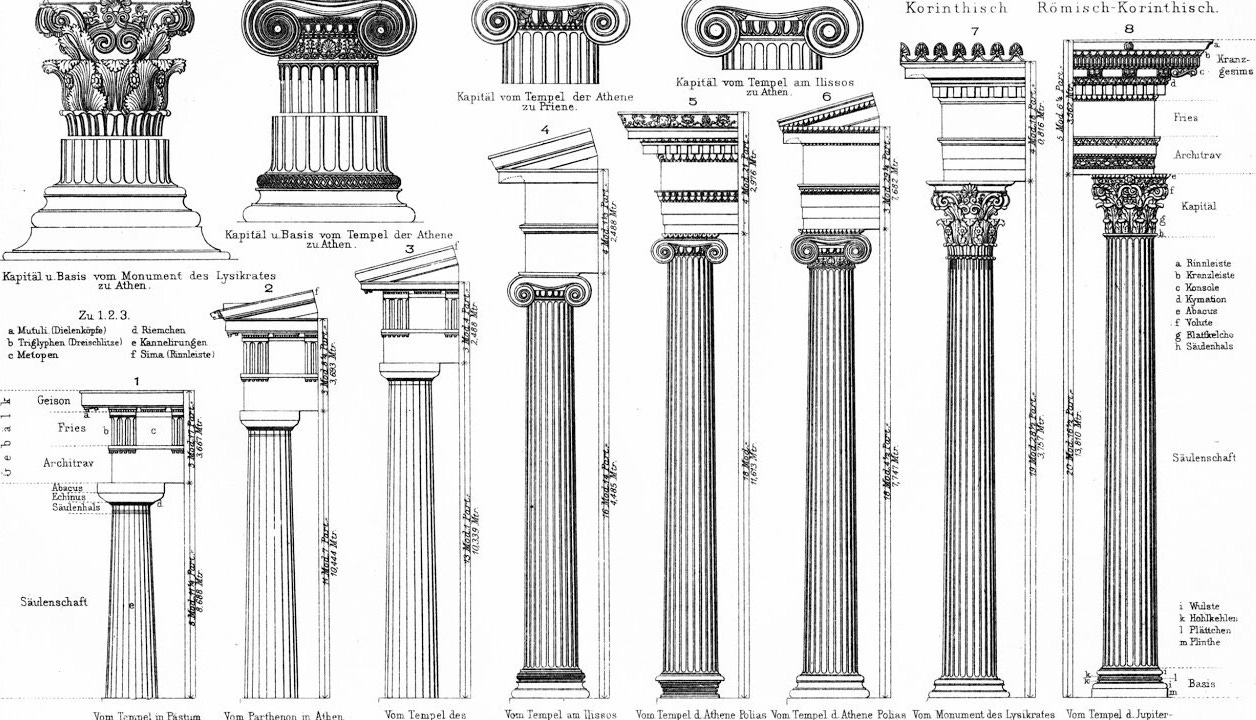

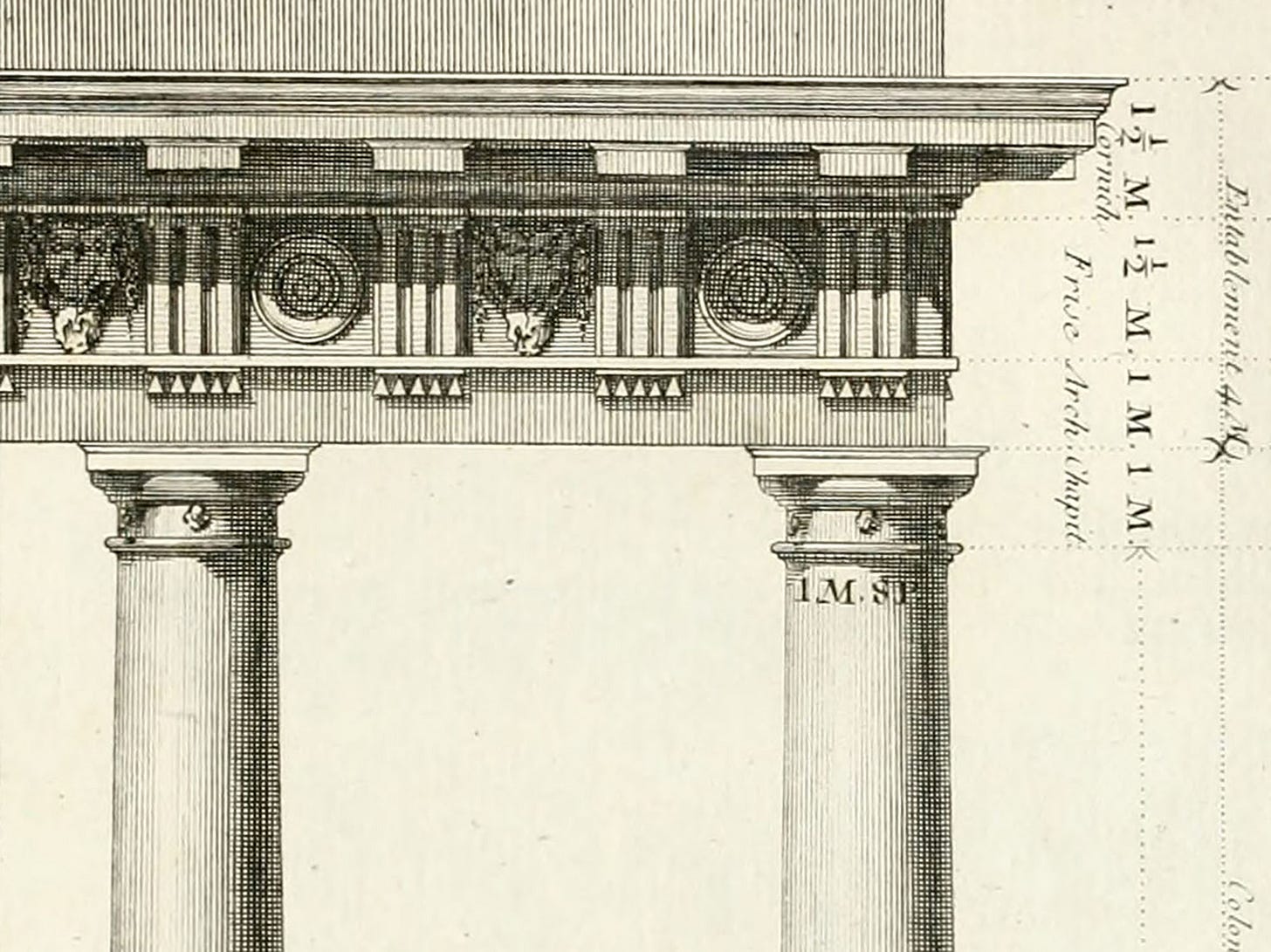

This principle is most clearly embodied in the classical orders—Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian—which function as a structured vocabulary, each with its own syntax of proportion, ornament, and spatial relationships. The application of order extends beyond individual columns and entablatures to the entire organization of buildings and urban spaces. From the articulation of façades to the sequencing of rooms and courtyards, order provides the logic that underpins classical architecture’s ability to communicate clearly and with purpose.

Principle II: Symmetry

Symmetry, much like balance in an argument or rhythm in verse, governs the equilibrium of architectural form. It ensures that architectural compositions resonate with a sense of stability and intention, reinforcing the innate human preference for order and predictability.

Bilateral symmetry, the most common type, establishes a mirroring of elements across a central axis, much like grammatical parallelism enhances clarity in language.

Radial symmetry organizes space around a central point, akin to the radial logic of certain mathematical equations or the structure of a well-formed narrative.

Translational symmetry, in which elements repeat along a linear axis, reflects the rhythmic progression seen in musical phrasing or poetic meter.

Beyond mere visual regularity, symmetry influences movement and spatial perception. A symmetrical façade welcomes the observer with a sense of repose and stability, while an interior arranged according to symmetrical principles offers an intuitive sense of orientation and flow. Just as coherent language fosters understanding, symmetry in architecture fosters a spatial dialogue between form and inhabitant.

Principle III: Proportion

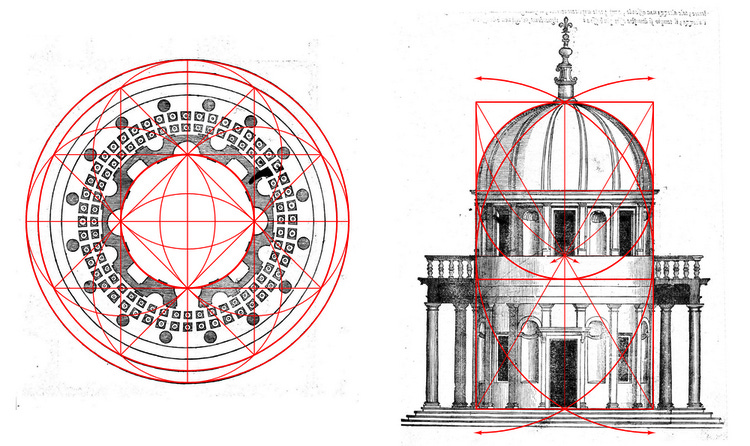

Proportion is the mathematical underpinning of architectural harmony, ensuring that relationships between parts are meaningful and intelligible. It is to architecture what meter is to poetry or harmony to music: an unseen but deeply felt order that governs composition. The classical tradition employs a variety of proportional systems to achieve balance and elegance:

The golden ratio (1:1.618), a recurring mathematical proportion in nature, art, and architecture, imparts an ineffable sense of harmony to structures.

Musical ratios, derived from Pythagorean harmonic theory, establish consonance between dimensions, much as musical intervals create auditory balance.

Human bodily proportions, articulated by Vitruvius and famously depicted in Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, ensure that architecture is attuned to the scale and rhythm of the human experience.

Proportion governs everything from the height and width of columns to the overall dimensions of rooms and façades, ensuring that each component relates meaningfully to the whole. A well-proportioned building, like a well-structured argument, achieves a coherence that is immediately grasped, even if its underlying rules remain implicit.

Principle IV: Harmony

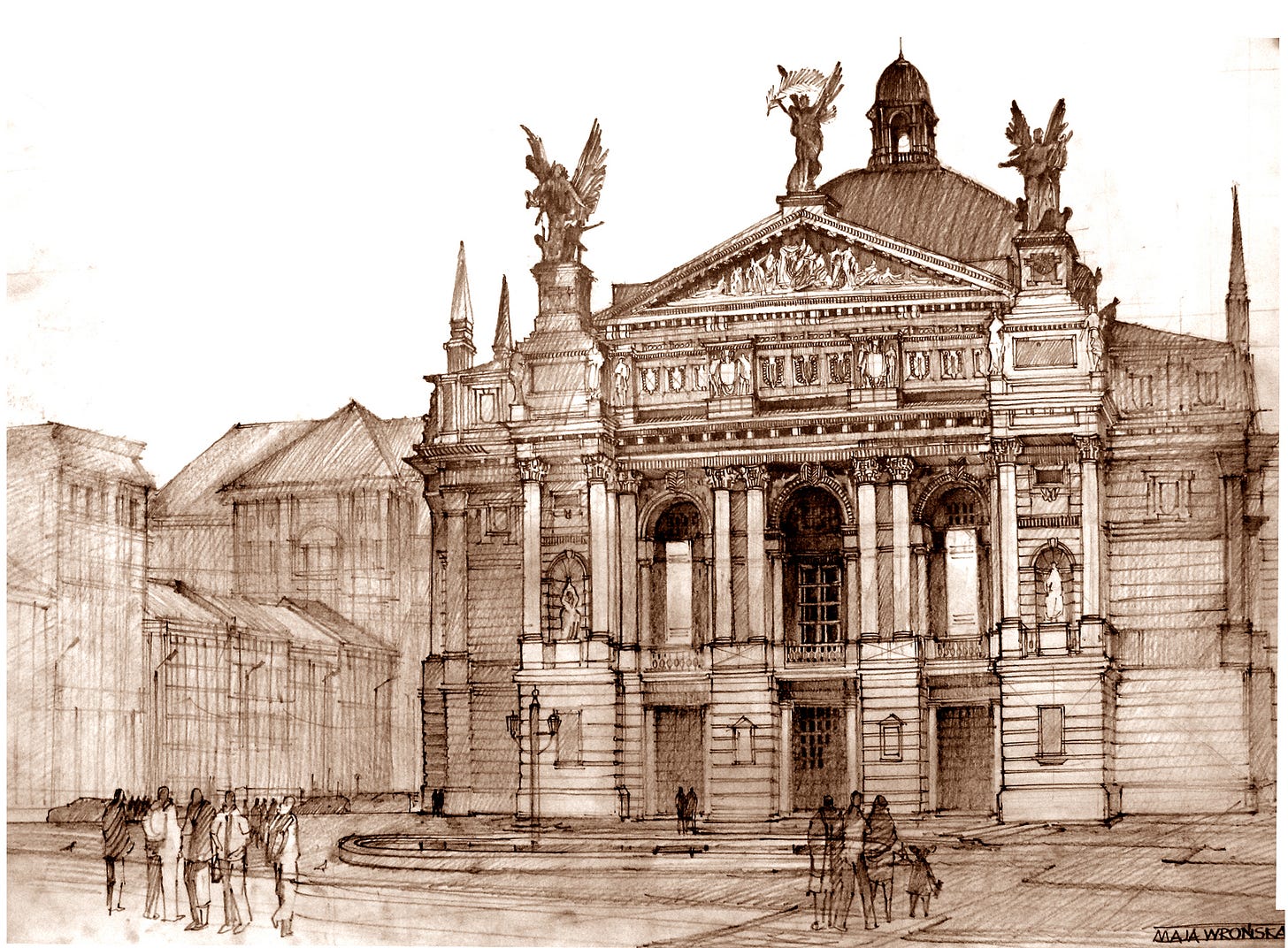

Harmony is the synthesis of diverse elements into a unified whole, much like the interplay of syntax, diction, and rhythm creates literary eloquence. It is the resolution of competing forces—solid and void, structure and ornament, mass and light—into a composition that feels both inevitable and effortless.

Achieving harmony requires a disciplined application of proportional relationships, a rhythmic arrangement of architectural elements, and a balance between structure and decoration. Just as a well-crafted sentence integrates clauses seamlessly, a harmonious building integrates disparate parts into a cohesive entity. Ornament must enhance rather than overwhelm, mass must be counterbalanced by open space, and complexity must be tempered by clarity. When executed successfully, harmony in architecture produces an experience akin to reading a masterfully written passage: a moment of recognition, of understanding, of aesthetic and intellectual satisfaction.

Principle V: Ornament

Ornament is architecture’s rhetorical flourish, its means of articulating structure, function, and meaning. Far from mere decoration, ornament serves as a visual grammar that reinforces architectural logic. Just as rhetorical devices in language clarify and emphasize meaning, classical ornament enriches the built environment by making its structural principles legible and engaging.

Structural ornament—such as capitals, entablatures, and moldings—clarifies a building’s tectonic framework, much as punctuation clarifies syntax in writing.

Decorative ornament, from acanthus leaves to egg-and-dart moldings, adds depth and texture, playing with light and shadow in a manner akin to poetic imagery.

Symbolic ornament, in the form of allegorical reliefs or inscriptions, embeds cultural and historical meaning, much like metaphor and allegory in literature.

Ornament serves as a bridge between the rational and the expressive, transforming abstract principles into tangible beauty. It ensures that architecture, like language, remains not just functional but meaningful, engaging the intellect as well as the senses.

The language of classical architecture, governed by order, symmetry, proportion, harmony, and ornament, is not a rigid formula but an evolving system of communication, one that has endured precisely because it is rooted in universal principles of human perception and cognition. Just as grammar structures language and mathematical laws structure the physical world, classical architecture structures space in a way that is intelligible, purposeful, and elevating. Whether in the austere dignity of a Doric temple, the refined elegance of an Ionic colonnade, or the exuberant complexity of a Corinthian capital, the classical tradition speaks across centuries, a silent witness to the human impulse to create order and beauty from the chaos of material existence.

Read Part I:

Next Saturday’s article (Part III) will explore the Classical Orders: Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Great article, thank you for publishing it. I hope many read it!