Beauty & The Grammar of Stone - Pt. I

Classical architecture functions not just as an art, but as a language—one that, if taught with rigor and insight, offers its learners a richer, more profound understanding of the world they inhabit.

The following is based on a mini-class demo I taught at a recent High School Parent Info Night at Cincinnati Classical Academy.

The principles of classical architecture are vital keys to understanding a deeper, almost forgotten order—an order of space, form, and proportion that once governed the way we built and lived. Classical architecture, like a language, speaks to us in the structure of columns and arches, the precision of geometries and ratios. It’s a language that, when understood, grants access to a kind of intellectual clarity, an aesthetic grammar that mirrors the syntax of language or the logic of mathematical equations. Just as students of Latin decode the structures of sentence and syntax, so too must students of classical architecture decipher the formal rules that underlie the design of buildings, comprehending not only how to construct with stone but how to read the deeper, universal principles that shape our built environment.

This is the subject of our inquiry: to explore how classical architecture functions not just as an art, but as a language—one that, if taught with rigor and insight, offers its learners a richer, more profound understanding of the world they inhabit. It is an education in how to read the world through structures. It is the deciphering of a syntax that governs not only the construction of walls but the arrangement of the universe. In this sense, classical architecture becomes not merely a subject to be studied but a way of understanding the language of the world, and perhaps more significantly, a means to speak back to it.

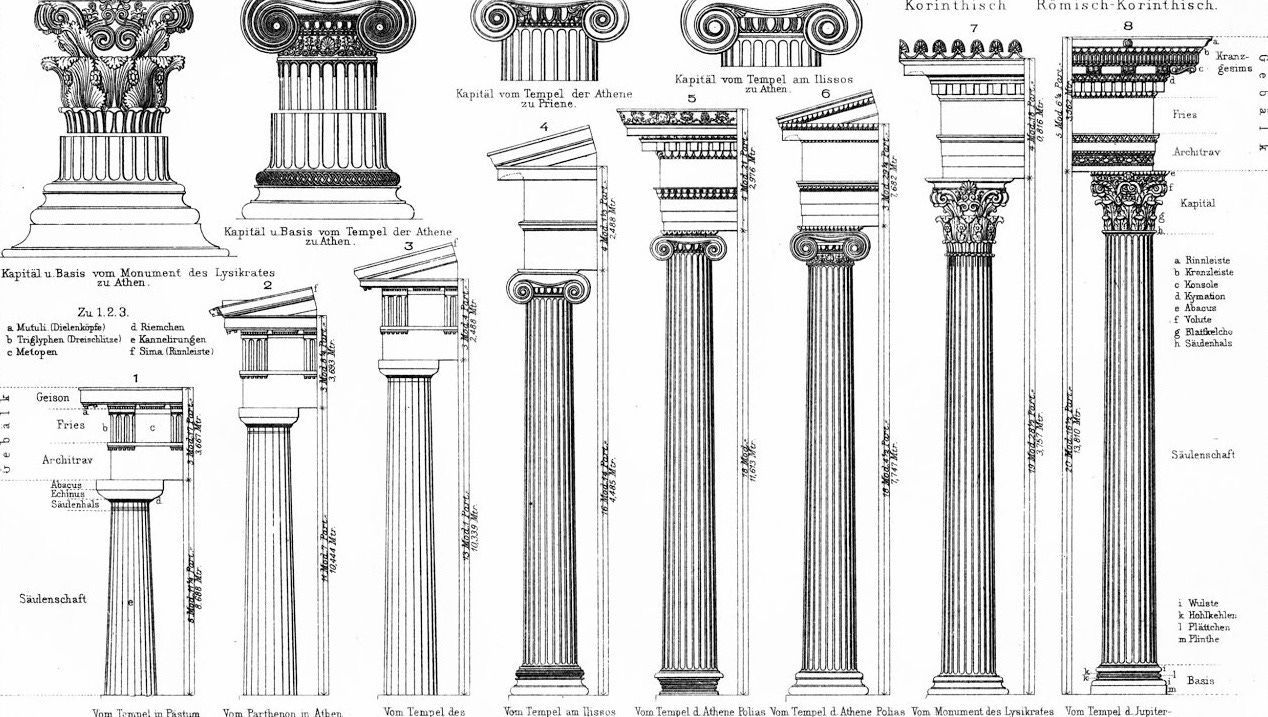

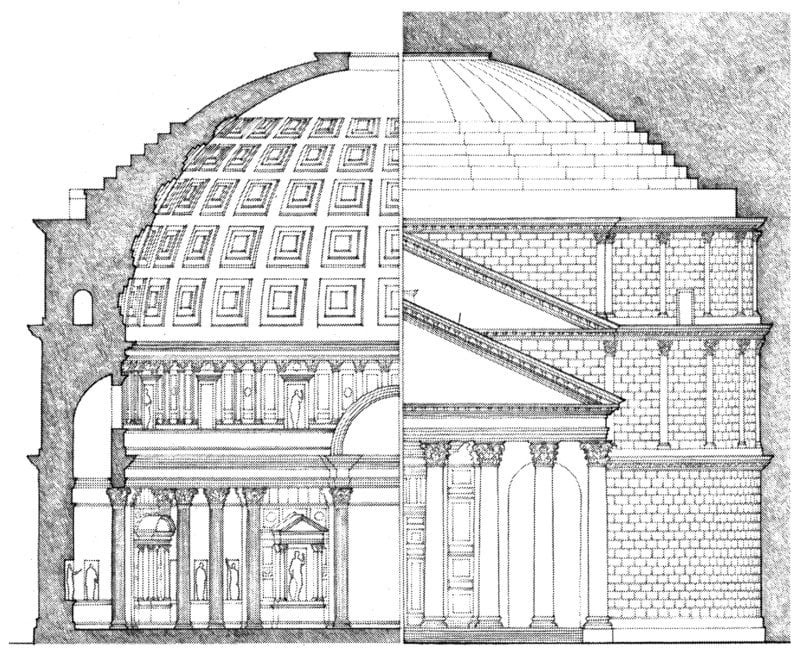

Consider the analogy of language. Just as one might learn to conjugate verbs in Latin or memorize the irregularities of French grammar, so too must a student of classical architecture learn to “conjugate” the elements of design. The column, the entablature, the pediment—they are not just forms pulled from some dusty past. No, they are tools, symbolic devices that make sense of the world’s chaos, organizing the intangible energies of human desire and ambition into visible, permanent structures. These tools have a syntax: the Ionic column versus the Doric, the semicircular arch versus the elliptical, the balance of weight and space that grounds the design as surely as a sentence relies on subject and predicate. Like the rules of grammar, the elements of classical architecture must be understood as integral parts of a whole system. Break the rules, and you risk distorting meaning; follow them, and the result is clarity—clarity of vision, of form, of space. The same can be said of a beautiful quatrain or an orderly equation.

In this way, classical architecture can be seen as a language not unlike Latin. A student of Latin does not merely memorize vocabulary words, but rather learns how these words interact within the larger framework of syntax and grammar. They learn how words function together to create meaning, how small shifts in structure can create entirely different outcomes, how the flow of a sentence depends not just on the words themselves but on their relationship to each other. So too must the student of classical architecture learn the ways in which columns, beams, and vaults interact with one another. The symmetry of the Corinthian column with its ornate foliage contrasts sharply with the clean, austere form of the Doric, but both belong to the same lexicon. Understanding how one style gives birth to another, how one form informs the next, requires an intuitive grasp of architectural grammar—just as understanding Latin demands a nuanced appreciation for its rules of syntax.

Moreover, just as the study of Latin unlocks the history of thought and culture, so too does classical architecture reveal the history of human society and intellect. It is the embodiment of culture’s intellectual evolution, from the geometric precision of the Greek temple to the soaring, harmonious designs of the Renaissance. It is an education in how different epochs have shaped the principles of beauty and order, how human beings have, over time, come to articulate their aspirations through material forms. The classical principles aren’t relics, but living evidence of the intellectual movements that birthed them: an intellectual grammar whose cadence can be traced across centuries, from the lofty ideals of ancient Greece to the grand visions of Palladio, Wren, and Jefferson.

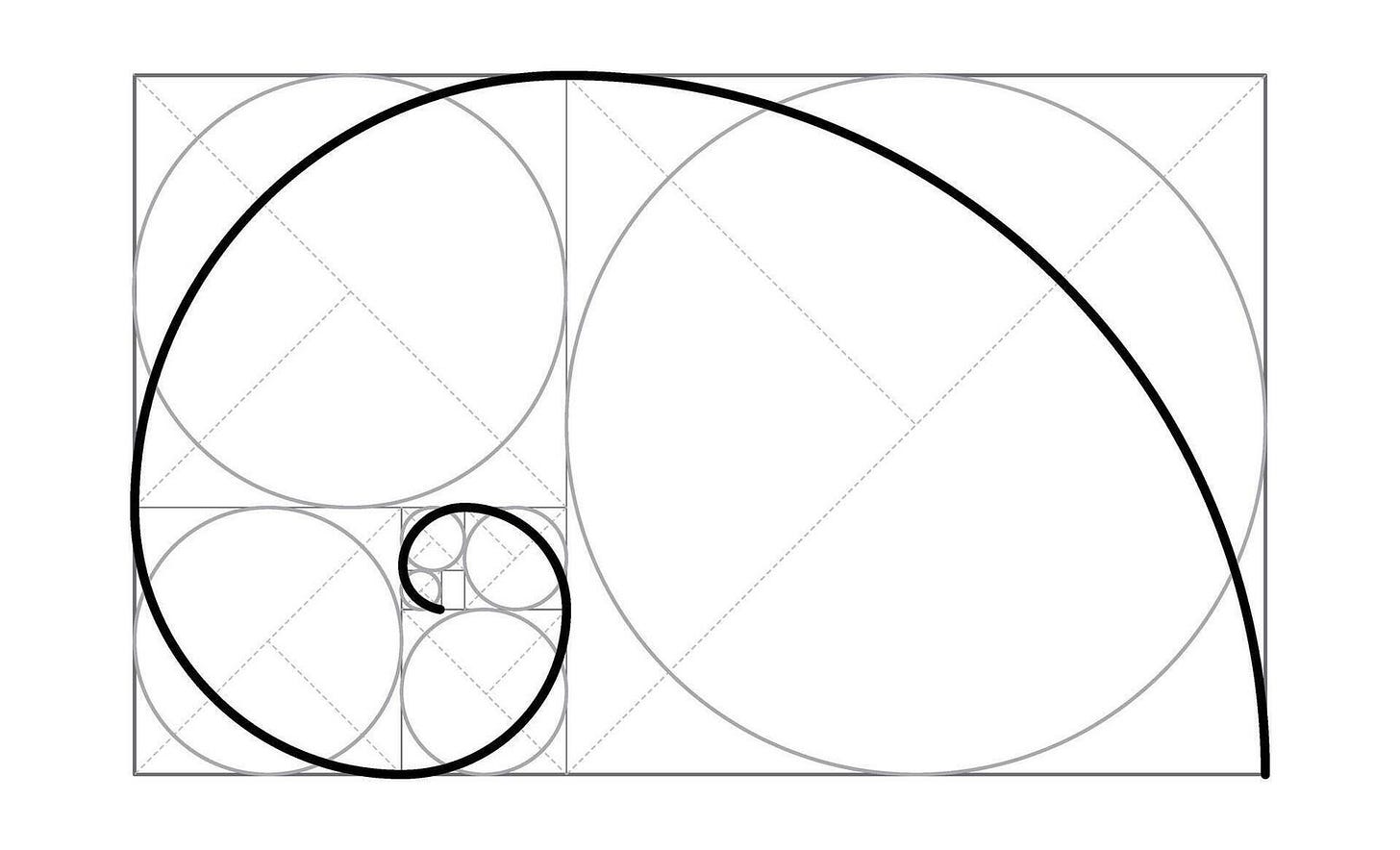

To introduce students to these principles is not so much to teach them how to design buildings, although they may one day go on to do that. It is to introduce them to a method of thinking, to a mode of inquiry that transcends architecture and permeates all human intellectual endeavor. The precision of a classical building’s proportions, the interplay of light and shadow across its surfaces, mirrors the precision of a mathematical proof. Mathematics itself, the purest of languages, relies on a careful order of symbols and operations to communicate a fundamental truth. In much the same way, classical architecture relies on a harmonious balance of form, function, and aesthetic to communicate a certain truth about human existence. Just as a properly balanced equation reveals a truth about the nature of numbers, so too does a well-proportioned building reveal truths about the relationship between the human body, the surrounding environment, and the cosmos.

In the study of classical architecture, we find a profound harmony between the world of art and the world of mathematics, between the poetic and the precise. The Doric column is not just a stylized form of decoration but a logical manifestation of the geometric principles that govern our reality. The proportions of a building, derived from the Fibonacci sequence or the golden ratio, resonate with the same mathematical elegance that drives the natural world. When students learn to recognize these patterns, they learn not only to read architecture, they learn to read the world itself.

And so, for educators in classical schools, teaching the principles of classical architecture is an invitation to show students the world through a new lens—a lens where geometry and poetry coalesce, where form and function converse, and where the lessons of the past are not just remembered, but brought into a new understanding. In teaching students to see architecture not merely as a physical discipline but as a language, they open the door to a fuller, richer comprehension of the world they inhabit, one that is as structured, precise, and beautiful as the language of Latin, or the harmony of a perfect equation.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Good article. I would not just say: “from the geometric precision of the Greek temple to the soaring, harmonious designs of the Renaissance”. But would keep it going to the grand buildings of 19th century Europe and 20th century USA. (Witness Penn Station, the New York Public Library and so many other buildings in the US.