The Subversive Art of Sentence Diagramming

A key to understanding language, to thinking deeply, and, perhaps, to finding a measure of beauty in the intricate, interconnected world of words

As language increasingly flows unexamined through digital shortcuts and fleeting conversations, the forgotten discipline of sentence diagramming offers a deliberate pause, a chance to see the machinery of words in motion. This subversive art, redolent of chalky residue and the creak of well-worn classroom floors, peels back the skin of language to reveal its sinews, tendons, and skeletal frame. To diagram a sentence is to examine the intricate architecture of thought itself, exposing the hidden scaffolding where subject leans into predicate and clauses weave their filigree of nuance and intent.

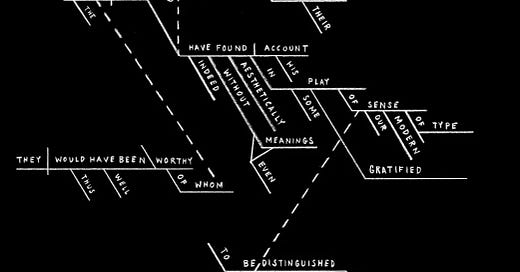

It is an exercise both maddeningly meticulous and beautifully transcendent, where the mundane grammar of daily speech unfurls into a vast latticework of logic and interdependence. Here, prepositions cling like ivy to their objects, modifiers dangle precariously, and conjunctions bridge the chasms between ideas, all laid bare, stark and luminous, under the unforgiving precision of diagrammatic lines. For the student, this is no mere academic exercise but a slow awakening to the mechanics of meaning, a revelatory act of peeling back layers until only the raw essence of human communication remains: structured, deliberate, and infinitely expressive.

Consider, first, the act of drawing the diagram. Here, the student is no passive recipient of information but an architect, laying down lines and branches, separating subject from predicate, dangling modifiers like precarious ornaments, and tethering conjunctions to the spine of meaning. In this quiet act of construction, an analytical mind is born. The sentence, once an opaque block of words, becomes a lattice of relationships: nouns nesting snugly in their subjects, verbs marching forward with transitive clarity, prepositions dangling their objects like keys to hidden doors. Language ceases to be a formless fog and reveals itself as a machine of almost mechanical precision, one that with practice a student can disassemble and rebuild at will.

Take, for instance, the humble declarative sentence: “The cat sat on the mat.” To the uninitiated, this is a string of mundane words. But to the diagrammer, it is an ecosystem. The subject—cat—claims the first perch on the horizontal line, the action—sat—its partner in predicate. Below, on the mat descends like the roots of a tree: the preposition on stretching its limb to clasp the object mat. Even here, in its simplicity, the diagram reveals an essential truth: the sentence is a world in miniature, a model of order. The student begins to see not just language but thought itself as structured, as something that can be analyzed, understood, and improved.

Then there is the pleasure—oh, let us not ignore the pleasure! The act of sentence diagramming, for those initiated into its mysteries, carries a tactile satisfaction akin to solving a puzzle or composing a melody. It is the joy of fitting pieces together, of teasing out hidden structures, of coaxing order from the chaos of words. To diagram a particularly complex sentence—say, one of Henry James’s labyrinthine constructs or a Biblical sentence sprawling with clauses and subclauses—is to wrestle with the sublime. Each branch and subordinate line drawn is a small triumph, a victory over the ambiguity of language.

Consider this longer example from Dickens: "It was the best of times, it was the worst of times, it was the age of wisdom, it was the age of foolishness." A student tasked with diagramming such a sentence faces a delightful challenge. The repetition of "it was" demands its own horizontal scaffolding, while each predicate nominative—"the best of times," "the worst of times"—branches off like tributaries from a mighty river. And what of the modifiers? "Of times" descends dutifully below its respective nouns, offering a cascade of meaning. Through this exercise, the student learns to untangle parallelism, to recognize patterns and contrasts. They are no longer reading passively; they are dissecting, questioning, comprehending.

The benefits of such a practice extend beyond mere grammatical fluency. To diagram a sentence is to cultivate a habit of mind that is analytical, precise, and unafraid of complexity. These are the same habits that underpin scientific inquiry, mathematical reasoning, and even ethical debate. The student who masters the diagram becomes adept at seeing relationships, at breaking down problems into their constituent parts. They learn that no idea is too complex to be understood if approached methodically. Moreover, they gain an appreciation for the elegance of language, its capacity to balance clarity and nuance, simplicity and intricacy.

In a world increasingly dominated by fragmented, bite-sized communication—texts, tweets, and emojis—sentence diagramming is a defiant assertion of depth. It reminds students that language is not merely a tool for conveying information but a medium for constructing thought. To understand a sentence in its entirety is to respect the mind that created it, to honor the centuries of linguistic evolution that shaped its form.

And yet, sentence diagramming is more than just a skill; it is a philosophy. It teaches that order can be found amidst disorder, that complexity can yield to clarity. In an era where so much of education is focused on "outcomes" and "metrics," diagramming offers something far richer: a process, an engagement, an intellectual adventure. It is a practice that rewards patience and persistence, that challenges students to look beyond the surface and delve into the structure of things.

So let us sing the praises of sentence diagramming, not as a quaint relic of bygone classrooms but as a vital tool for modern minds. Let us invite students to take up their pencils, to draw their lines, to see the hidden skeletons of their thoughts. For in this seemingly simple act lies the key to understanding language, to thinking deeply, and, perhaps, to finding a measure of beauty in the intricate, interconnected world of words.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico) and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Also, if you want to play this game, you’ll need the greatest coach ever, IMO.

Her name: Phyllis Davenport. Her playbook: Rex Barks.

Go forth and conquer, fellow subversives. I’d love to see some diagramming graffiti in small towns across America (fully washable, of course.) https://amzn.to/4ccnziP

This made me subscribe. Well done.