The Subversive Art of Observation

Classical education’s commitment to seeing—seeing reality—is a kind of resistance, not merely to error, but to the machinery that institutionalizes it.

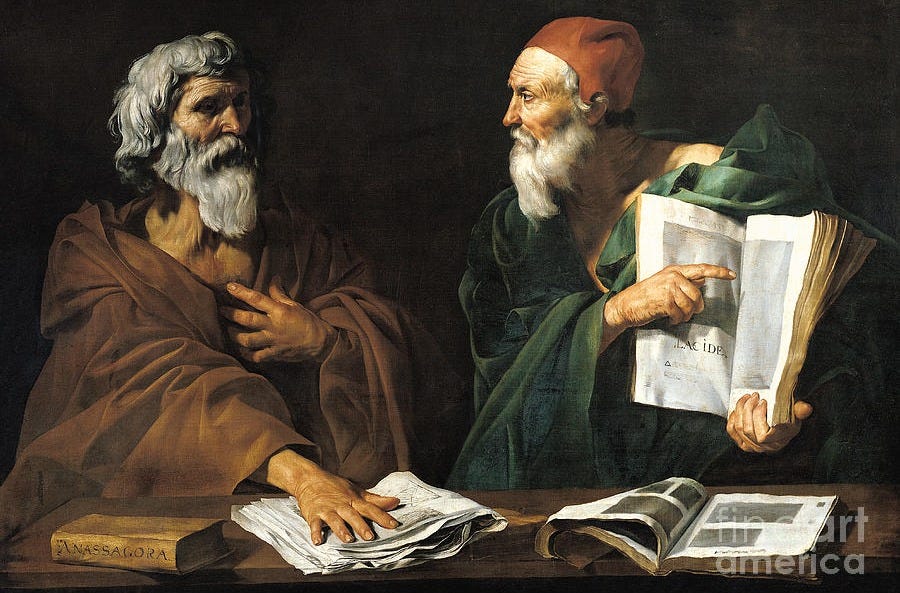

In the age of curated feeds, AI hallucinations, and pedagogical gamification, the notion that thought begins not in theory but in observation—careful, disciplined, often unglamorous observation—is practically heretical. And yet, Classical education insists on just that: look first, think later. Start not with a rubric, not with a lens—Marxist, feminist, decolonial, intersectional—but with the thing itself, stubborn and irreducible, humming in the raw light of being. The world, not your idea of the world.

This, of course, is bad news for the cartographers of ideology, for whom the map must always dictate the terrain. Better to begin with a grand narrative, to fit children out with interpretive goggles, corrective lenses for the “problem” of reality. Tell them what to expect and they will learn to see it. Oppression, everywhere. Hegemony, always. Their own interiority, commodified and spotlighted, becomes the only permissible subject of inquiry. The self as terminal field of study. And yet, the Classics whisper otherwise: look outwards, child—toward the stars, the stones, the syllogisms.

This rebellion—quiet, Socratic, enduring—begins in grammar, not grievance. In the slow parsing of Latin clauses, the patient attention to iambic pentameter, the geometry of Euclid, that ancient meditator on lines and limits. It is not flashy. It does not perform well on TikTok. But it builds habits of mind—reverence for form, suspicion of abstraction, a nose for nonsense—that once acquired are devilishly hard to shake. Here lies the true subversion. Not in slogans or sit-ins, but in contemplation. In the act of beholding what is, rather than what should be.

Classical education’s commitment to seeing—really seeing—is a kind of resistance, not merely to error, but to the machinery that institutionalizes it. Bureaucratic pedagogy demands outcomes, data points, deliverables. The classical mind demands truth. Hence the tension. You cannot standardize wonder. You cannot mass-produce insight. You cannot “scale up” the Republic. The virtues cultivated in a classical education—prudence, temperance, courage, justice—refuse to be measured by the same metrics that govern quarterly benchmarks and social-emotional learning objectives.

And so the ancient arts find themselves exiled, not by irrelevance, but by their stubborn refusal to comply. Logic is too rigid. Rhetoric too hierarchical. History too uncooperative with contemporary moral fashions. Worse still: the Greeks ask hard questions and refuse to provide comforting answers. The Hebrews demand holiness. The Romans discipline. Together, they call the bluff of the modern classroom, where empathy is weaponized and knowledge subordinated to “lived experience.”

To observe, in the classical sense, is to submit—to nature, to tradition, to the real. It is an act of humility, often confused in our age with passivity. But no, the observer is not passive. He is vigilant. He knows that perception is always under threat—from ego, ideology, distraction. The student must train his mind like an athlete: to discern the essential, to resist the immediate, to stay with the object until it yields its meaning.

But tell this to the educational technocrat, whose dashboard lights up with analytics and whose curriculum is designed to align students with “competency frameworks” drawn from corporate HR departments. For such a system, the child is not an intellect, but an input. “Critical thinking” becomes a brand, untethered from logic or evidence, a kind of reflexive dissent aimed only at approved targets. Inquiry becomes compliance in disguise. And yet—and yet—the classical tradition stands there, quietly unyielding, like some eccentric grandfather in a wool suit, quoting Aristotle at dinner, reminding you that thinking well is not the same as thinking differently.

In this light, the return to classical education is not nostalgic—it is revolutionary. Not a longing for the past, but a reassertion of first principles. It teaches that reality is intelligible, that truth is not merely constructed, and that beauty, far from being a bourgeois illusion, is a clue to the deeper order of things. It challenges students not to express themselves, but to transcend themselves.

This is a hard sell in a culture drunk on novelty, in a civilization that has outsourced its memory to machines and its judgment to algorithms. But it is precisely in this derangement that the old ways find their urgency. We must teach our children not to emote but to see. To follow the thing to its source. To begin not with theory but with wonder, not with grievance but with gratitude. To see what is there—truly there—before trying to change it.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

My takeaways from this article:

One quote that particularly resonated with me was: “We must teach our children not to emote but to see. To follow the thing to its source.” This succinctly captures the author's call for an education rooted in observation rather than ideology.

The central argument—that children should be taught how to think rather than merely what to think—is compelling. In “the age of curated feeds, AI hallucinations, and pedagogical gamification,” the author laments that students are increasingly presented with knowledge filtered through a mediator, resulting in a kind of intellectual dependency. Learning, in this view, becomes less about direct engagement and more about passively receiving pre-processed content.

By contrast, the author suggests that Classical education fosters independence of thought. Its emphasis on form, structure, and foundational texts trains students to “look first, think later.” The scaffolding is designed to cultivate attentiveness, discipline, and a deeper understanding of the world as it is—not merely how we interpret or feel about it.

That said, I wonder whether the article draws too stark a contrast between Classical and modern education—creating what feels like a false dichotomy. On one side, Classical education is presented as wholly virtuous, cultivating timeless values such as prudence, temperance, courage, and justice. On the other, modern approaches are depicted as ideological, shallow, and emotionally manipulative, where “empathy is weaponized and knowledge subordinated to ‘lived experience.’”

This raises an important question for me: Who defines the values upheld in a Classical education? Even within that tradition, gatekeeping still occurs—someone is always setting the curriculum, marking the papers, and shaping the student’s worldview. Are we not still relying on interpreters, albeit with a different canon?

Perhaps the most fruitful path lies not in choosing between Classical and modern models, but in asking what gave rise to each. By understanding the historical and cultural conditions that shaped them, we might discover new possibilities—ways to navigate the emerging horizon rising from the uncertainty and disruption of our present moment. By making the different models oppositional we risk overlooking the short comings of both. The habits of mind we cultivate early on must also support a lifetime of learning, unlearning, and re-seeing.

This is a good, true, and beautiful apologetic for classical education. Thank you for writing it.