The Formative Books of Abraham Lincoln

An education that bears striking resemblance to the curricula of American classical schools: narrow in volume, deep in substance, grounded in language, moral instruction, and historical example.

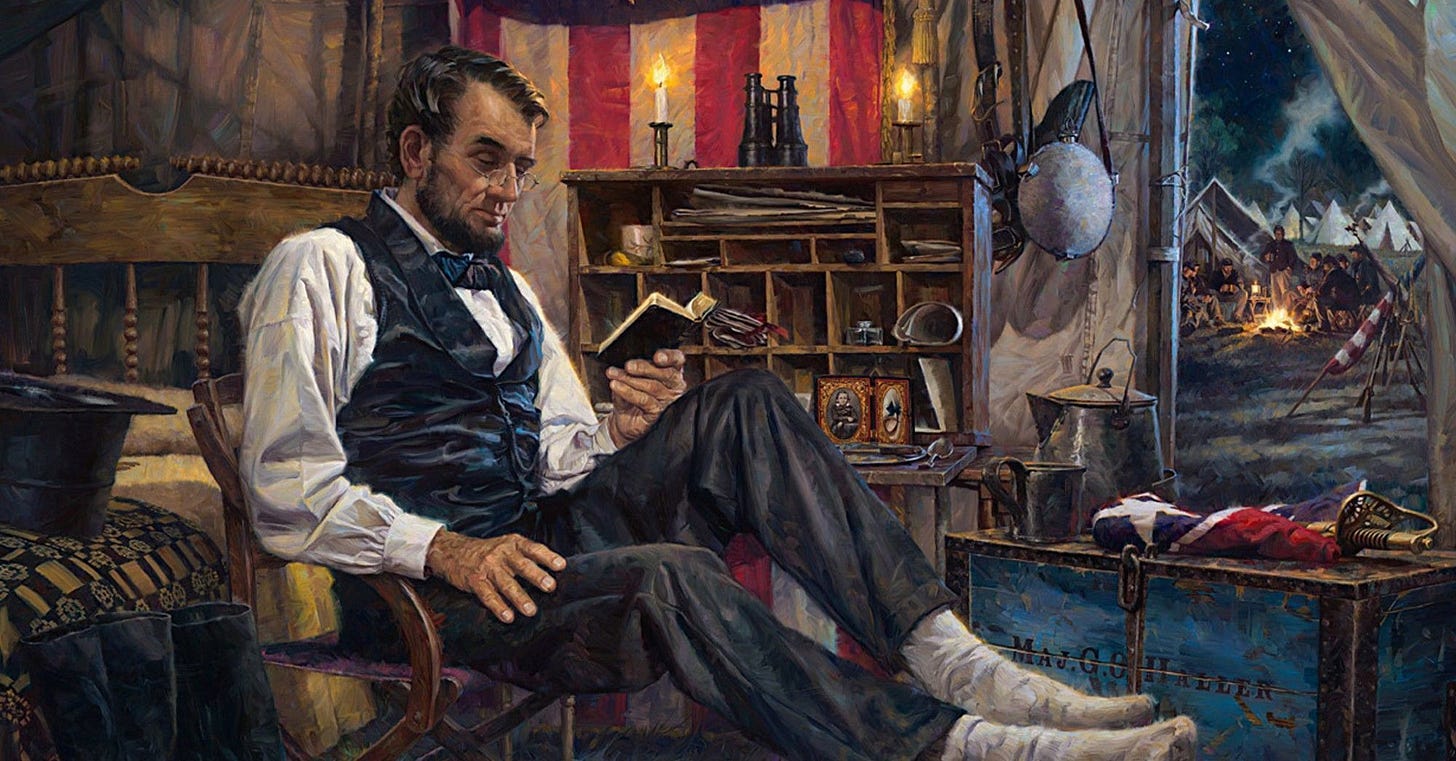

The early life of Abraham Lincoln unfolded neither within the walls of any institutional academy nor under the strict regimen of tutors or governors, but amid the plain necessities of frontier subsistence, in the coarse cabins and smoky interiors of Kentucky and Indiana, where education arrived, if it arrived at all, through the medium of borrowed books and fading print, through repetition, through memory, through slow, solitary reading by firelight.

And yet, what the future sixteenth president received, through accident or providence, was an education that bears striking resemblance to the curricula of American classical schools: narrow in volume, deep in substance, grounded in language, moral instruction, and historical example. These were not books selected for their entertainment value or novelty, but for their capacity to form the mind, to shape the moral imagination, and to direct the will.

The books were few. And each one mattered.

Aesop’s Fables

Among the first and most enduring was Aesop’s Fables, a collection of ancient moral tales attributed to a Greek slave whose identity is largely mythic, but whose stories became canonical in both Europe and the U.S., reprinted in dozens of editions for schoolchildren and recited aloud in schoolhouses, parlors, and pulpits. For Lincoln, as for many children educated in the classical mode, Aesop served not simply to entertain but to instruct. The tales teach economy of language, the structure of narrative, the principle of cause and effect. They reward attention and penalize haste. In their anthropomorphized dialogues—e.g., the fox and the grapes, the tortoise and the hare—one finds, reduced to elemental form, the classical virtues: prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice. In many classical schools throughout the ages, these fables formed part of the moral catechism of early education, passed on not for their charm but for their enduring clarity of judgment. Lincoln, who would grow to deliberate carefully, found in these tales an early schoolmaster.

The Bible

The Bible, particularly the King James Version, stood next to it, though not only as a religious document. In Lincoln’s home, it was likely the most substantial and perhaps the only book to be read with regularity. Its rhythms, cadences, images, and phrases, translated into English with a reverence for literary grandeur, entered Lincoln’s mind in childhood and never left. Here, again, we find parallels with classical education as it was understood in the early decades of the American republic and well into the twentieth century: Scripture not merely as doctrine, but as literature, as source of moral law, as repository of allegory and typology. For Lincoln, whose prose would come to echo the tone of Ecclesiastes and the Sermon on the Mount, the Bible was a source of ethical reasoning and poetic speech. In the Second Inaugural, Lincoln paraphrases both Psalms and Matthew; in the Gettysburg Address, he wrote sentences whose architecture mirrored the parallelisms of Hebrew poetry.

The Life of George Washington

Alongside Scripture stood The Life of George Washington, most likely the version penned by Mason Locke Weems, a work that scholars now recognize as hagiography rather than history, but which in its time functioned as moral biography. For Lincoln, the narrative of Washington’s virtue, his self-restraint, his honesty, and his solemn dignity as both soldier and statesman, offered a model of conduct and character. Though later generations would rightly critique Weems’s stylizations, the Life of Washington served its formative function: it provided a boy with an image of ordered liberty, of civic virtue realized through self-governance and personal restraint. Classical schools frequently use such lives—of Washington, Franklin, and others—not to teach history per se but to inculcate a sense of belonging to a moral and political tradition.

The Pilgrim’s Progress

The Pilgrim’s Progress by John Bunyan was another of Lincoln’s books, and it too featured prominently in the libraries and recitations of classical schools, both Catholic and Protestant, well into the modern era. An allegory of the soul’s journey through temptation, suffering, and endurance, Pilgrim’s Progress emphasized the trials of moral formation. Its characters—Christian, Faithful, Hopeful—bear their names as signs of their function. The narrative structure, episodic and symbolic, invites young readers to see their own lives as moral journeys. Lincoln, who would often speak in metaphors drawn from travel, from burden, from passage and arrival, was undoubtedly marked by this book’s central conviction: that life is a struggle toward the good, and that salvation, whether spiritual or civic, comes only through constancy of purpose.

Robinson Crusoe

Robinson Crusoe, by Daniel Defoe, was a book of a different kind, but no less essential. For Lincoln, the tale of a man shipwrecked and forced to build, by hand and reason, a world from nothing, surely resonated with his own life. Raised amid the rawness of an untamed land, Lincoln would have seen in Crusoe’s labor the logic of American settlement, the dignity of industry, the virtue of independence. Crusoe is not a romantic adventurer; he is a rational being who records his thoughts, improves his condition, and forms a society where none existed. In the curricula of classical schools, Crusoe often serves as a bridge between the moral allegories of youth and the more complex narratives of modern manhood. It provides a vision of the self as capable, deliberative, and resilient. These, too, were the traits Lincoln cultivated.

The Complete Works of Shakespeare

Finally, and perhaps later, came The Complete Works of Shakespeare, though it is not clear precisely when Lincoln encountered the Bard of Avon. What is clear is that Lincoln read him deeply, repeatedly, and aloud. The tragedies in particular—Hamlet, Macbeth, Lear—formed a permanent part of Lincoln’s internal landscape. The speech patterns of his letters and addresses reflect a mind shaped by Elizabethan cadence; the themes of his public life—ambition, conscience, betrayal, fate—found analogues in the histories and dramas of the Bard. In classical education, Shakespeare stood as the culmination of literary formation: the highest achievement of the English tongue, and the most profound exploration of the human soul in action. For Lincoln, the plays were not simply entertainments, but companions in solitude and mirrors of political life.

This small library—Aesop, the Bible, Washington, Bunyan, Defoe, and Shakespeare—was not eclectic. It was coherent. It formed a unified tradition. It spoke of virtue, struggle, duty, and mortality. It was the education of a classical school, rendered not in rows of desks, but in the stillness of an evening, in the margins of work, in the solitude of a boy with a book.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

This is wonderful. I'd love to see a recommended reading list for high school grade by grade!

Very interesting. It’s fun to use the “light” you’ve provided to illuminate what I know of President Lincoln’s life. For us today, Lincoln is a more distant historical figure than was Washington for him.

While your primary vocation is to shape young minds, my challenge is to “make up for” opportunities lost over 67 years. I attended a Catholic high school a few years after it dropped Latin as a required course. My religious education was of the balloons-and-banners, folk music era. In middle age I returned to far greater orthodoxy, yet the gaps remain.

I first read Tale of Two Cities with any seriousness in my 40s. I did manage to pick up and love Dante’s Comedia around the same time. Augustine’s Confessions, too, is a later-in-life love.

I was much helped by correspondence with the late Reverend James Schall. His The Mind that is Catholic, The Regensburg Lecture, Another Sort of Learning, and The Order of Things, among others have shaped my worldview.

Most influential in my life was a tenth-birthday gift from my grandmother – a paperback boxed set of The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings. I know that Tolkien’s literary genius and deep Catholic faith were at works even during my most wayward wanderings. Naturally this led me to read virtually the entire CS Lewis corpus – fiction and non-fiction.

So, here’s a challenge, perhaps not for you but for some of my fellow CCR travelers: How to fill in for a life not-perfectly spent? I find reading poetry nearly impossible, except oddly, for Dante. Milton? Fuggedabout it. Iliad and Odyssey? Pretty tough. This is sad, because my son-in-law has an English lit Masters from Oxford. A very patient young man!

As I’m still working, I lack the time to fill in all the cracks. The Compleat Works of Shakespeare are probably only a faint dream. Or hallucination.

Thoughts?