The Classical Teacher as Architect of Civilization

Cue the gasps: authority isn’t enlightenment’s villain—it’s its backbone. A master doesn’t hand an apprentice tools and expect a Parthenon; he teaches, corrects, leads.

Here's an important question: What, precisely, is the role of the teacher?

The classical model posits not what modern critics dismissively call the “sage on the stage”—a term that diminishes the teacher to a mere performer of knowledge—but rather a philosopher, one whose lamp illuminates the path not only for the students who tread behind but for himself as well. The philosopher-teacher is forever seeking, with no assurance but the conviction that wisdom is not handed down in inert packets of data but wrestled with, argued over, grappled against in the noisy amphitheaters of human inquiry. To reduce such a noble calling to a derogatory caricature is to fundamentally misunderstand the profound intellectual relationship between teacher and student that has shaped civilization since antiquity.

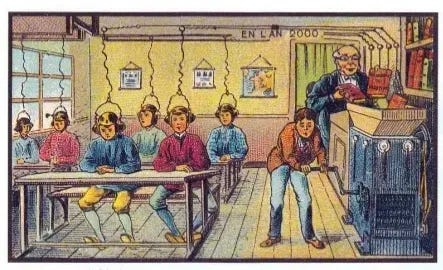

The problem: Modern pedagogy, with its fixation on “student-centered learning,” fancies itself an egalitarian utopia, its gurus mouthing incantations of “empowerment” and “self-discovery” as if students, left to their own devices, might reconstruct Euclid from the ether, stumble into Homeric verse in between glances at their digital mirrors, and deduce the principles of rhetoric through the osmosis of vibes.

The teacher in this unfortunate model becomes a curator of resources, a spectral presence resigned to the periphery, like some forlorn museum docent whose job is merely to gesture vaguely in the direction of the exhibits while students meander in reveries of non-commitment. Yet what is lost in this abdication of authority is not merely the gravitas of the educator, not simply the unbroken lineage stretching from Socrates to Aquinas to Newman, but the actual structure by which thought coheres into civilization.

Socrates, it is instructive to note, did not abandon his students to the mercies of the agora, did not leave them to scavenge for scraps of wisdom among the sophist charlatans. He engaged them in dialectical battle, driving them beyond the comfort of easy answers into the vertiginous landscapes of doubt and inquiry.

The teacher in the classical tradition does not, as some would have it, impose doctrine with the blunt instruments of dogma but like Socrates in the agora, teacher and pupil advance together through the intricacies of knowledge, their shared task illuminated by dialectic’s torch rather than doctrine’s cudgel.

Authority, the bogeyman so despised by modern pedagogues, is not the enemy of enlightenment but its necessary scaffold. A master craftsman does not hand his apprentice a collection of chisels and expect him, through unstructured tinkering, to rediscover the Parthenon. The master leads, instructs, corrects—not as a tyrant but as a guide (no, not the cliche guide on the side) whose knowledge is the hard-won fruit of discipline and devotion. To return to the classical ideal is not to resurrect some imagined golden age of authoritarian didacticism but to reaffirm the sacred trust between teacher and student, a trust that demands not the anarchy of self-directed learning but the rigorous, humbling discipline of apprenticeship to wisdom itself.

To return to the classical ideal is not to resurrect some imagined golden age of authoritarian didacticism but to reaffirm the sacred trust between teacher and student, a trust that demands not the anarchy of self-directed learning but the rigorous, humbling discipline of apprenticeship to wisdom itself.

To restore the teacher to his rightful place is to rescue education from the slow corrosion from relativism, the erosion of rigor, the dissolution of knowledge into mere opinion. It is to acknowledge that the mind, left alone, does not spontaneously generate truth like a petri dish in a warm lab, but must be trained, guided, sharpened against the whetstone of superior intellects. It is to declare that wisdom is not a private possession but a shared pursuit, a torch passed from generation to generation, each flame kindled by the careful hand of one who has already braved the dark.

Thus, the classical teacher does not relinquish authority; he wields it—wisely, humbly, in the service of truth. And in that wielding, he does not diminish his students but ennobles them, granting them not the illusion of self-sufficiency but the genuine inheritance of intellectual and moral formation. For the path to knowledge, like all great roads, is not a solitary wandering but a guided journey, led by those who have walked it before and are unafraid to walk it again, for the sake of those who follow.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Yes, thank you. It occurred to me that the wisdom you mention can be “a shared pursuit, a torch passed from” friend to friend. It may be ad hoc and intermittent, non the less, it is an opportunity for those of us who no longer attend formal schools. You are our “classical teacher.”

I sure do agree with you. Thank you for sharing your immense wisdom. Would have loved to of had a principal like you.