Shakespeare's Syllabus for the Education of the Soul

The Bard's "Seven Ages of Man" is not merely a meditation on the passage of time; it is a reminder that wisdom is a journey through the shifting landscapes of human experience.

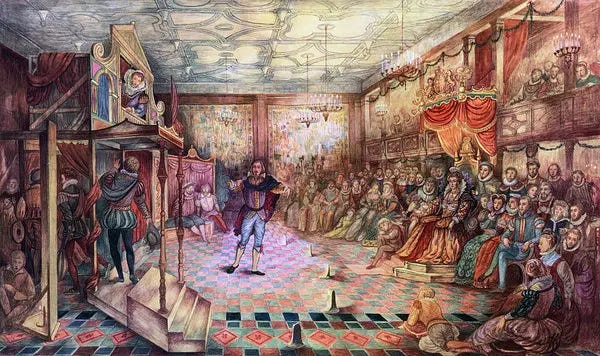

Amid the dense foliage of Shakespeare’s As You Like It, a pastoral comedy rich with courtly caprice and rustic levity, emerges a monologue so pointedly unpastoral that it feels almost out of place, a sudden eddy in the otherwise sun-dappled stream of merriment. Jaques, the perpetually melancholic philosopher, steps forth to unfurl his soliloquy, an anatomy of human existence carved into seven definitive acts. “All the world's a stage,” he declares, reducing our species to mere players, unwitting marionettes dancing to the jerking strings of Time. Yet within this grim fatalism lies a peculiar wisdom, a road map, albeit a circuitous one, to navigating not just life but the education of the soul.

First, the infant: helpless, squalling, a creature of pure need and primal instinct. Here lies a truth so obvious it’s often missed: life begins in utter dependence, and education must start in humility. The infant’s open mouth and clenched fists are metaphors for a voracious, unformed potential. To educate at this stage is not to impose knowledge but to nurture curiosity. The wisdom imparted here is embryonic, and yet it holds the key to all later stages: to learn, one must first accept the limits of one’s understanding, must cry out into the void and wait for an answer. The foundation of wisdom, Shakespeare hints, begins not in certainty but in the willingness to absorb the world’s overwhelming polyphony.

And then the schoolboy, reluctantly trudging toward his lessons, a satchel slung over his shoulder, his face scrubbed clean of delight. Here, Shakespeare’s humor curdles, and education becomes a farce, a grim parody of what it might aspire to be. The boy’s whining resistance is no mere childish caprice; it is the first spark of a struggle that will haunt him through every subsequent age: the tension between freedom and discipline. But there’s wisdom in this reluctance, too, a kind of proto-rebellion against a system that would grind the joy of discovery into mechanical drudgery. Education in this stage must navigate this paradox, to instill discipline without extinguishing curiosity, to transform resistance into engagement, to teach the boy not merely to conform but to think. The satchel, heavy with books, must also carry the seeds of wonder.

Education must instill discipline without extinguishing curiosity, transform resistance into engagement, and teach the child not merely to conform but to think.

Next, the lover, sighing like a furnace, composing odes to eyebrows and scrawling hearts on the margins of textbooks. At this stage, education shifts inward, becoming a theater of emotion. The lover is intoxicated by beauty, consumed by longing, and it is here that literature and art offer their profoundest lessons. Through poetry and music, the lover learns to articulate what is otherwise inexpressible. Shakespeare acknowledges the foolishness of this age but doesn’t dismiss it. There is wisdom in foolishness, after all, in the unbridled passion that pushes the self beyond its narrow confines. To educate the lover is to refine this passion, to teach discernment without stifling ardor, to guide the wild furnace of feeling into the creation of something lasting: a love of truth, beauty, and virtue.

And then the soldier, “Full of strange oaths, and bearded like the pard.” Here, Shakespeare’s wisdom takes a darker turn. The soldier’s world is one of conflict, ambition, and sacrifice, a stage where ideals clash with the brutal realities of power. To educate the soldier is to confront the duality of courage and recklessness, to temper valor with prudence, and to instill a sense of justice that transcends personal gain. This is the age of civic education, of learning the art of compromise and the value of serving a cause greater than oneself. Yet Shakespeare, ever skeptical of human pretensions, reminds us that ambition often leads to self-destruction. The soldier’s wisdom lies not in conquest but in restraint, in recognizing that true strength is the ability to wield power without succumbing to it.

The justice follows, “In fair round belly with good capon lin’d,” a figure of authority and reason. This is the age of judgment, of synthesis, where the fragments of earlier education coalesce into wisdom. The justice embodies the Socratic ideal of knowing what one does not know, of listening more than speaking, of dispensing not merely the law but justice. To educate the justice is to cultivate a sense of moral clarity, an understanding that truth is rarely simple and that every judgment carries the weight of human consequence. Shakespeare’s portrayal is both idealistic and ironic; the justice, with his comfortable belly and worldly airs, is prone to self-satisfaction. The wisdom of this stage, then, is tempered by humility, by the constant recognition that even the wisest are fallible.

Then comes the sixth age, “The lean and slipper’d pantaloon,” a figure of decay and obsolescence. Here, education becomes reflection, a reckoning with the choices made in earlier stages. The pantaloon’s shrinking frame mirrors the narrowing of possibilities, yet Shakespeare does not paint this age as entirely bleak. There is a quiet wisdom in renunciation, in the acceptance of life’s transience. To educate at this stage is to guide the soul toward gratitude and grace, to teach that the waning of physical strength need not diminish the vitality of the spirit.

Finally, the last scene of all: “Sans teeth, sans eyes, sans taste, sans everything.” The ultimate surrender, where education ceases to be about learning and becomes a preparation for letting go. Here lies the paradoxical wisdom of Shakespeare’s vision: that life’s final act, though stripped of all outward dignity, holds the potential for a profound inner liberation. To live well, the play suggests, is to prepare for this moment, to cultivate not just knowledge but the courage to face the inevitable with equanimity.

Jaques’ “Seven Ages of Man” is not merely a meditation on the passage of time; it is a syllabus for the education of the soul, a reminder that wisdom is not a fixed destination but an odyssey through the shifting landscapes of human experience. Each age, with its peculiar challenges and triumphs, offers a lesson—a stage in the lifelong drama of becoming fully human.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human (Angelico) and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

I am currently reading two great Shakespeare books: Shakespeare, the Man Who Pays the Rent by Judi Dench; and then Thinking Shakespeare by Barry Edelstein. He the great Shakespeare acting coach and she the best actress. It seems like having the actor’s stage knowledge is most helpful for those English majors among us.