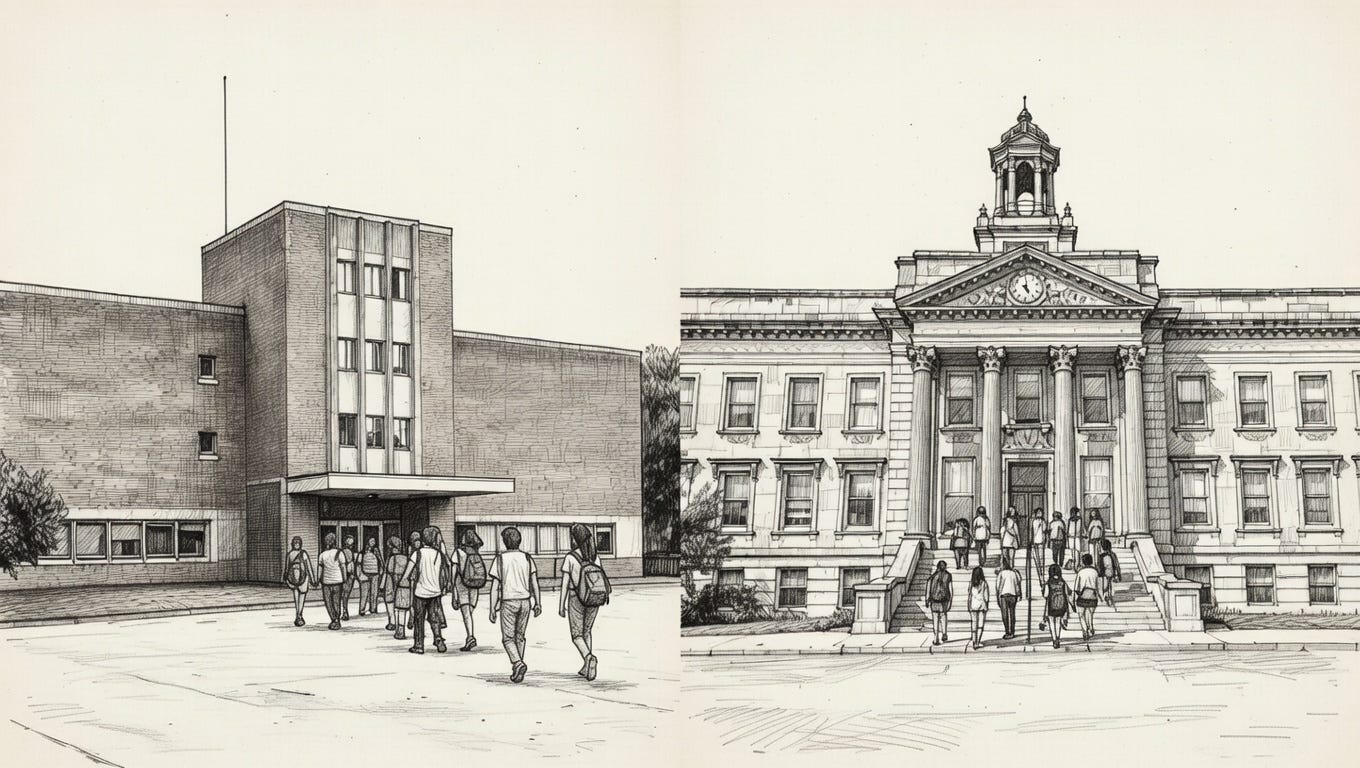

School Architecture Educates. Or Miseducates.

What do our school buildings say about human dignity? Do they whisper, “You are small in a meaningless system,” or do they say, “You are being initiated into something worthy of love”?

Tom Wolfe’s From Bauhaus to Our House is many things at once: a cultural autopsy, a comic rant, a moral fable, and—perhaps unexpectedly—a penetrating meditation on education. Though the book is ostensibly about modern architecture and its discontents, Wolfe’s sharpest barbs land squarely on the kinds of buildings in which we raise children. Long before “learning environments” became a buzzword and long after anyone thought to ask whether a school should look like a prison a a factory Wolfe understood something essential: architecture educates. Or miseducates. Every day.

Wolfe’s central complaint is well known and gleefully overstated, as all good Wolfean complaints are. Modernist architecture, born in the rarefied theories of European avant-gardes—the Bauhaus chief among them—arrived in America stripped of human affection. What remained was an austere, joyless style obsessed with ideology and allergic to beauty. The result, Wolfe argues was domination: a new priesthood of architects telling ordinary people what they ought to like, live in, and learn within.

Nowhere is this more troubling than in schools.

Wolfe doesn’t write a chapter entitled “Why Modern Schools Are a Disaster,” but he hardly needs to. His critique of modernism’s hostility to ornament, scale, warmth, and memory applies with particular force to educational buildings. Schools, after all, are not neutral containers. They are moral environments. They form habits of mind long before a child opens a book.

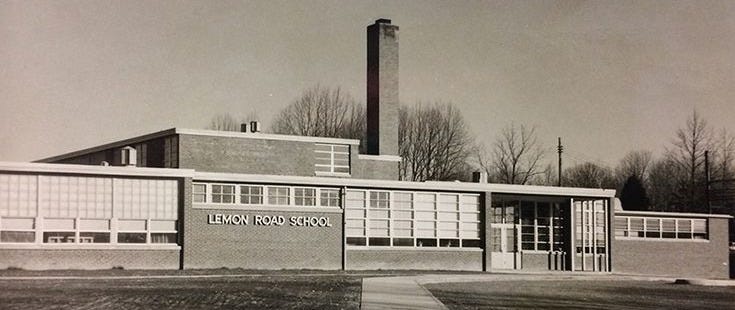

And yet, as Wolfe delights in pointing out, twentieth-century school design often seems animated by a barely concealed contempt for childhood itself. Out go pitched roofs, welcoming entrances, legible hallways, and humane proportions. In come flat roofs that leak, windows that don’t open, concrete walls the color of despair, and corridors that feel less like places of learning than minimum-security holding pens. If education is meant to initiate the young into a civilization, one wonders which civilization these buildings were hoping to introduce.

My new book, The Subversive Art of a Classical Education: Reclaiming the Mind in an Age of Speed, Screens, and Skill-Drills, is now available on Amazon.

Wolfe’s genius lies in both identifying this problem and in skewering the pretensions behind it. Modernist architects, he notes, spoke endlessly of function while producing buildings that functioned poorly. They rejected symbolism while imposing their own severe and unmistakable ideology. They claimed to serve the masses while showing open disdain for popular taste. Schools designed under these assumptions invariably reflected the same contradictions. They were meant to be efficient and forward-looking but ended up strangely hostile to the students they were built to serve.

What makes From Bauhaus to Our House such a pleasure is that Wolfe never lets theory escape comedy. He treats architectural manifestos the way Swift treated political pamphlets: with mockery sharp enough to draw blood. When he describes the way American institutions—universities, school boards, municipalities—embraced modernist design as a marker of sophistication, one can’t help but think of school administrators proudly unveiling a new building that looks like a parking garage and costs twice as much as promised. The joke, Wolfe suggests, is always on the children.

Implicit throughout is a humane vision of architecture rooted in tradition. Wolfe understands that children learn best in places that feel ordered and beautiful, places that suggest permanence. A school that looks like it belongs to a long story invites students to imagine themselves as part of one.

This is why From Bauhaus to Our House remains so relevant, especially for educators. Wolfe reminds us to look up—quite literally—at the walls around us. What do our schools say about truth, beauty, and human dignity? Do they invite reverence or indifference? Do they whisper, “You are small in a meaningless system,” or do they say, “You are being initiated into something worthy of love”?

Wolfe’s answer is unmistakable, and his warning still rings true. When we build schools that deny beauty, history, and human scale, we should not be surprised if students emerge restless and uninspired. Buildings cannot save education—but they can certainly sabotage it.

Playful, polemical, and profoundly serious beneath the laughter, From Bauhaus to Our House is a defense of the idea that the spaces where we teach should themselves be teachers. Wolfe may be exaggerating—he always is—but like all great satirists, he exaggerates in the direction of truth.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Subversive Art of a Classical Education (Regnery, 2026) and other books.

My family enjoys playing a road trip game called: "Prison or School?" The object of the game is to guess which of the two you're looking at as you drive by. It's a very difficult game.