How to Develop Immunity to Manipulation

Why are tech titans afraid of students reading primary sources? They develop the one skill algorithms can't replicate: the ability to think for themselves.

There’s a reason your child’s history textbook weighs six pounds but contains almost nothing worth remembering. There’s a reason the original documents that shaped Western civilization have been replaced by cheerful summaries written at a fifth-grade reading level. There’s a reason students can graduate from elite universities without ever reading a single complete work by the founders of their own republic.

The reason isn’t pedagogical. It’s strategic.

Silicon Valley understands something that most educators have forgotten: the person who encounters ideas directly owns them. The person who receives ideas pre-interpreted merely rents them. And a population of renters is far easier to manipulate and manage than a population of owners.

Consider what happens when a sixteen-year-old opens “Federalist No. 10” and reads Madison’s actual words about faction, representation, and the dangers of direct democracy. This student must slow down. The sentences don’t yield to skimming. The arguments don’t announce themselves with helpful subheadings. There are no discussion questions at the end of each paragraph, no vocabulary lists, no cheerful graphics breaking up the text.

He must think.

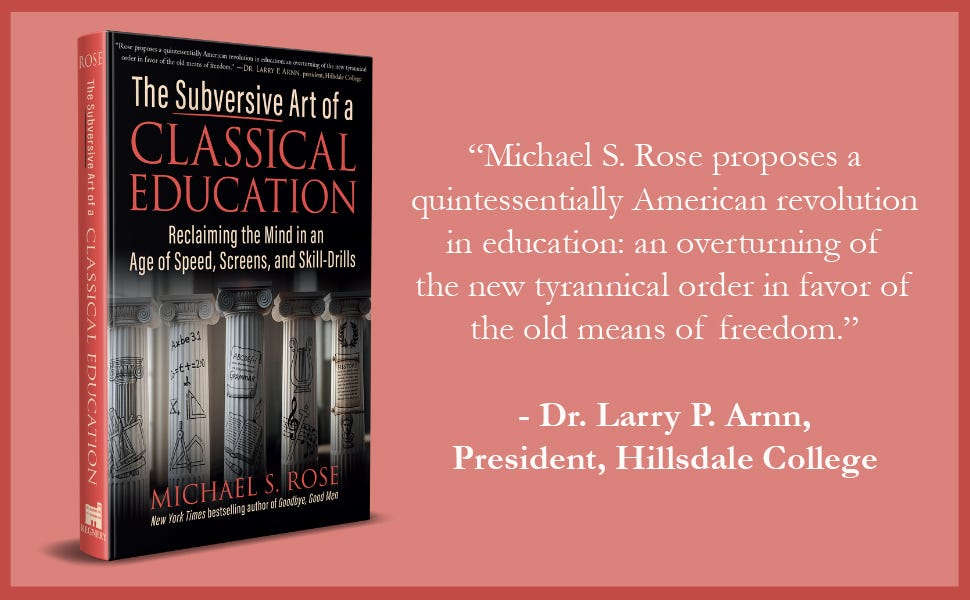

My new book, The Subversive Art of a Classical Education: Reclaiming the Mind in an Age of Speed, Screens, and Skill-Drills, is now available on Amazon. This book is the culmination of years spent leading a classical school and witnessing firsthand how tried and true perennial practices of learning offer the most powerful resistance to the forces fragmenting our children’s minds and souls.

He must follow an extended argument across multiple pages. She must hold competing ideas in tension. He must distinguish between what Madison says and what he’s been told Madison says. He must do the one thing the algorithm can never do for him: he must carefully contend with the text until he understands it.

This is precisely what terrifies the architects of our digital age.

The algorithm serves you what you already believe. It predicts your preferences based on your past behavior. It curates your reality to maximize engagement, which is to say, to minimize genuine thought. The algorithm needs you passive, predictable, and perpetually scrolling. It cannot tolerate the person who has learned to think by reading hard things slowly.

This is why textbooks have replaced primary sources with predigested summaries. This is why literature classes increasingly replace Shakespeare with contemporary young adult fiction. This is why history courses offer themed units on social movements rather than careful chronological study of original documents. The explicit justification is always accessibility, relevance, or engagement. The practical effect is always the same: students learn to consume interpretations rather than generate them.

Watch what happens in a classroom where students read textbook summaries of the Constitutional Convention versus one where they read Madison’s notes directly. In the first room, students absorb the approved narrative. They might discuss it. They might critique it. But they’re always responding to someone else’s framing, someone else’s emphasis, someone else’s conclusions.

In the second room, students confront the messiness of the actual debate. They see the compromises, the contingencies, the competing visions that somehow cohered into a governing document. They discover that history is not a morality tale with predetermined heroes and villains but a human drama requiring intellectual independence. They learn that understanding requires more than memorizing talking points.

They learn to think for themselves. And this, more than any particular conclusion they might reach, is what makes them dangerous to any system that depends on predictable response patterns.

Classical education’s insistence on primary sources is intellectual self-defense. When students spend years reading original texts—the Federalist Papers, yes, but also Plutarch, Dante, Douglass, Lincoln’s speeches, Supreme Court opinions, the Gettysburg Address without the helpful paragraph explaining what Lincoln “really meant”—they develop an immunity to manipulation.

They learn that complexity is normal, that great minds disagree, that truth emerges through argument rather than announcement. They discover that the hard work of understanding cannot be outsourced to an app, a summary, or an algorithm. They become adults who can encounter an idea, evaluate its merits, and form their own judgment without first checking what they’re supposed to think.

This is why Silicon Valley funds coding boot camps but not classical schools. This is why tech billionaires endow programs teaching students “how to learn” while quietly sending their own children to low-tech schools emphasizing Latin and logic. They understand perfectly well what they’re doing. They’re ensuring their children join the class of owners while training everyone else’s children to be renters.

The choice before us is not between old books and new technology. It’s between raising children who can think and raising children who can only consume. Between forming minds that generate understanding and minds that await instructions. Between citizens and users.

The counterrevolution begins with a single sentence on a page, read slowly, understood deeply, and owned completely. Everything the algorithm fears fits in a book.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Subversive Art of a Classical Education (Regnery, 2026).

The Ministry of Truth must be reckoned with. Besides its dandy 5th-grade summaries, it uses soul-deadening textbooks and slippery AI chatbots. At least some AIs hyperlink to the primary sources.

Many primary sources are accessible (Laura Ingles Wilder), some are not, and these require applied effort due to length, vocab, syntax (Shakespeare). The student who applies the effort will achieve outsized returns. I've viewed a live teacher in person as vital for the student to apply the effort.

What are the best options for the self-taught student who needs encouragement to understand a difficult primary source or for a homeschooling parent?

So grateful for your articles. Another benefit of classical education is meaningful timeless relationships with ourselves and others.