Dopamine & Data: The Infinite Feed

Artificial intelligence has now learned the secret recipe of attention itself. It is the world’s most patient student of human weakness, and it is being trained, every second, by our scrolling thumbs.

In the dim glow of a thousand small rectangles, the next generation is being raised on dopamine and data. The machines are learning what makes us watch, what makes us linger, what makes us laugh, and—most dangerously—what keeps us from turning away. Artificial intelligence has now learned the secret recipe of attention itself. It is the world’s most patient student of human weakness, and it is being trained, every second, by our scrolling thumbs.

Already, the average twelve-year-old spends more time on a screen than in school, and what he sees there is becoming curiously frictionless—content that slides by without pause or resistance, designed so seamlessly that it asks nothing of him but attention. The days of clunky algorithms recommending whatever was “trending” are over. The new systems don’t just guess at your taste; they compose it. These AIs can generate videos, music, memes, and micro-stories designed specifically for you, in your dialect and emotional register. They can spin up a cartoon series that only you will ever watch, populated by characters whose voices, expressions, and pacing are tuned to your private preferences (viz. MIT Media Lab). The experience will be seamless, eerie, and irresistible.

If that sounds hyperbolic, consider what TikTok’s algorithm accomplished without true generative AI: a machine-learning model that could, with minimal data, predict with alarming accuracy what each user wanted to see next. Now imagine that same engine armed not just with the ability to recommend content but to create it in real time. No actors, no writers, no studios—just a system synthesizing the most pleasurable visual stimuli known to the human brain, one second at a time.

This is the frontier we now approach, with the nonchalance of a civilization that has confused “engagement” with happiness. The corporate euphemism for addiction has always been engagement. But if today’s feeds are heroin, tomorrow’s will be fentanyl.

The generation most at risk—Gen Alpha, and the one coming after it, Gen Beta—will never know a world without such personalization. For them, entertainment (better understood as infotainment) will not be a product they choose; it will be a mirror that reshapes itself endlessly to their impulses. To call this “content” hardly does it justice. It will be companionship, a synthetic intimacy that knows your emotional rhythms better than your parents do.

Limiting “screen time” is a quaint defense against an infinite feed that can adapt its tone, form, and morality to any constraint.

For parents, the old rules will fail. Limiting “screen time” is a quaint defense against an infinite feed that can adapt its tone, form, and morality to any constraint. Tell a system to make videos that feel “educational,” and it will deliver slick parodies of learning—endless streams of soothing pseudo-knowledge with just enough cognitive friction to seem virtuous. Tell it to be “wholesome,” and it will wrap its addictions in moral sentimentality.

The truth is that AI doesn’t care whether we become wiser or duller. It cares only about metrics. It’s all about attention and monetization. Its loyalty lies with whoever programs it to extract the most human time from the fewest human hours. The great perennial philosophical question—“What is good?”—has been replaced by “What performs?”

And yet, there is a tragic brilliance in this. The human brain has always been hungry for story and recognizable pattern. AI is merely fulfilling that appetite with superhuman efficiency. The problem isn’t that the machine is too smart. It’s that we have no shared vision of what ought to satisfy us. When art, play, and conversation are all subsumed into the logic of optimization, culture itself begins to collapse inward.

We may, in time, look back at YouTube and Netflix with nostalgia—as primitive, even charmingly clumsy platforms. Their flaws left room for boredom, and boredom, paradoxically, is the last refuge of the human mind. Boredom is what drives us outdoors, toward friendship, books, and wonder. It is what reminds us that the world is not a simulation.

What can be done?

What can be done? Regulation, maybe—but no government agency can legislate the human craving for amusement. The only meaningful resistance may come from a cultural reawakening: parents, educators, and institutions reasserting that the goal of childhood is not to be entertained, but to be formed. We must restore a sense of interiority—of silence, stillness, and thought.

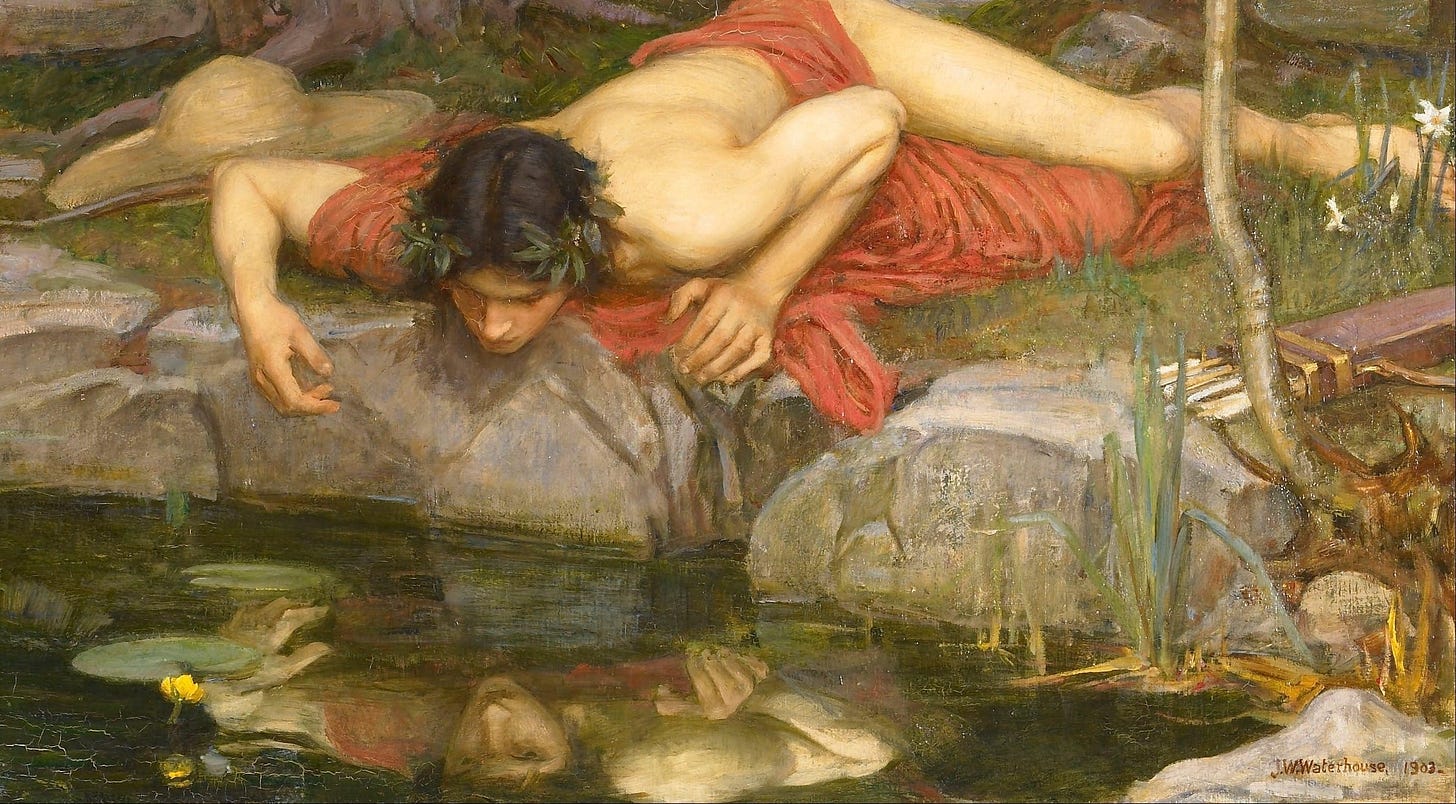

If we fail, Gen Alpha and Gen Beta will be lost in the literal sense: submerged in a digital tide so perfectly pleasurable that they will have no reason to come up for air. And by the time we notice, they may not even remember that there was ever a world above the surface.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His next book, The Subversive Art of a Classical Education, will be released by Regnery in January, 2026.

Thanks, Michael. I’ll let others draw parallels to Lewis’ That Hideous Strength and other prophetic works. Paul Kingsnorth’s new book, which I’ve not yet read but have followed his precursor essays, postulates demonic invasion via “the Internet.” I take Satan as a literal truth (others are free to feel differently), his thesis and yours make alarming sense.

Coincidentally, today’s The Catholic Thing essayist, Francis X. Maier, considers the works of Christopher Lasch. Two dense quotations accompany the article. The first is from The Revolt of the Elites (1995):

"People increasingly find themselves unable to use language with ease and precision, to recall the basic facts of their country’s history, to make logical deductions, to understand any but the most rudimentary texts, or even to grasp their constitutional rights. The conversion of popular traditions of self-reliance into esoteric knowledge administered by experts encourages a belief that ordinary competence in almost any field, even the art of self-government, lies beyond the reach of the layman."

The second is from The Minimal Self (1984):

"A culture organized around mass consumption encourages narcissism. . .not because it makes people grasping and self-assertive but because it makes them weak and dependent. It undermines their confidence in their capacity to understand and shape the world and to provide for their own needs. . . .Narcissism [involves] a loss of selfhood, not self-assertion. It refers to a self threatened with disintegration and by a sense of inner emptiness."

Your piece here homes in on the mechanics underpinning this phenomenon. It remains to be seen how we’ll respond. Possibilities include:

• Morlocks and Eloi on an accelerated timescale

• The Matrix

• The Butlerian Jihad

I struggle to formulate a useful posture and approach. I’m old enough to turn into a cranky old man (turn into one?). I fear for the world my grandchildren are beginning to encounter.

I’d appreciate your thoughts, particularly as your vocation is to the young and maturing.

I’ll close with a final excerpt from Maier’s essay. He cites the “sainted” John F. Kennedy in 1962. It disturbs me not only for its core message, but more alarmingly for how its animating ideas anchored the education I’ve received (engineering, MBA):

“…most of the problems, or at least many of them that we now face, are technical problems, are administrative problems… they deal with questions which are beyond the comprehension of most men.”

I have no doubt persons from long ago pre-literate culture would be alienated by our lack of being-in-the-world just as much as we find the near future’s ai hermeticism alienating. What it means to be human has never been static.