Discerning Beauty in a Fractured World

To love the beautiful is to yearn for the infinite—to stand on the edge of eternity and, like Moses on Sinai, glimpse a glory that no words can fully convey.

Dostoevsky’s simple proclamation that “beauty will save the world” hangs in the metaphysical air like a half-formed chord, a symphonic fragment waiting for resolution. What is this beauty that wields such salvific power? Is it a physical form, a Platonic ideal, or a whisper from eternity encoded in the shimmer of a sunset or the vaulted arches of a Gothic cathedral? To answer, one must first plunge into the classical triad of goodness, beauty, and truth, those ancient signposts pointing toward the infinite. Beauty, in this triumvirate, is the siren that seduces the soul toward higher realities, a radiant invitation to transcend the squalor of mere material existence. But how do we discern beauty in a fractured world, where the sublime is too often drowned in the cacophony of cynicism and kitsch?

The classical tradition sees beauty not as a subjective whim but as an objective reality—a harmony of parts ordered toward their proper end. Whether in the golden section proportions of an Ionic column or the swelling lines of a symphony, beauty reveals itself in the interplay of symmetry, proportion, and clarity. This is why the ancients could gaze upon nature—each tree, river, and star arranged in a cosmic choreography—and see in its grandeur the fingerprints of the divine. To them, beauty was not an escape but a bridge, a portal through which one might glimpse the eternal truths veiled by the mundane.

To define beauty, one might invoke Aristotle’s Metaphysics, where the Philosopher describes it as “that which, when seen, pleases.” Yet this pleasure is not the cheap thrill of the banal or the gaudy; it is a profound recognition of order, purpose, and fittingness. Consider the Parthenon, standing against the Athenian sky in austere magnificence, each column calibrated to align with an almost divine rhythm. Its design reveals not human ego but a striving to reflect the eternal: the beauty of mathematical precision yoked to spiritual aspiration. Or take Dante’s Divine Comedy, where the beauty of language and structure mirrors the moral and metaphysical order of the universe itself. Here is beauty as a revelatory force, drawing the soul upward through the concentric spheres of being toward the face of God.

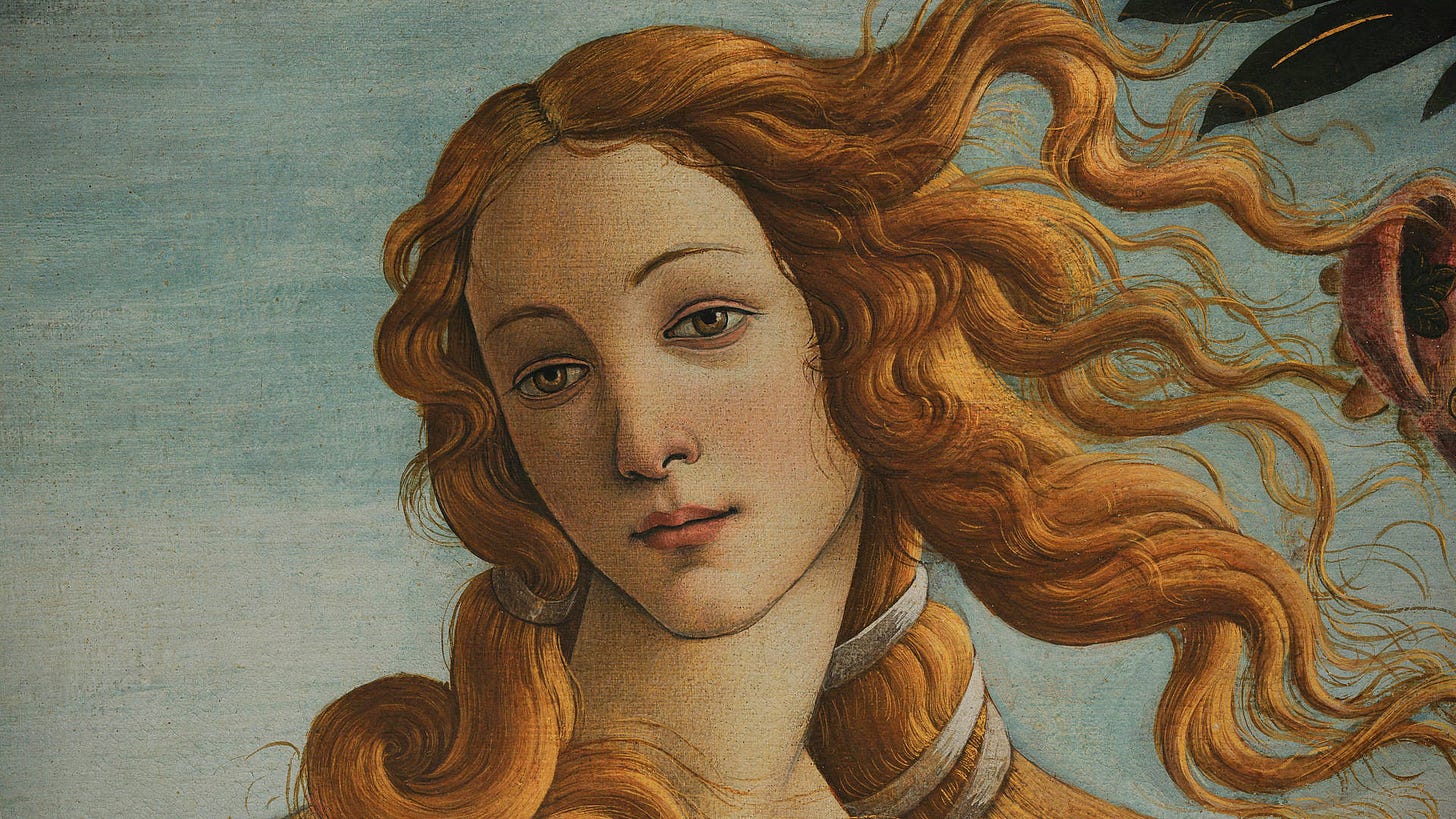

Today, the search for beauty is as urgent as ever, for it is beauty that calls us out of ourselves. It is found in people whose lives reflect virtues luminous as stained glass, their integrity a work of art forged in the crucible of suffering. It is glimpsed in the natural world, where alpine peaks rise like hymns to the heavens, and meadows bloom with an exuberance that speaks of an unexhausted creative love. It is in the works of human hands: the piercing realism of a Caravaggio, where light cleaves through shadow like grace breaking into a darkened soul; the solemn grandeur of Handel’s Messiah, where the soaring chorus “For unto us a child is born” carries listeners into realms that defy mere reason.

Architecture, too, remains an enduring locus of beauty. The ribbed vaults of a Gothic cathedral lift the eye—and the heart—heavenward, their intricate stone lacework a meditation on the infinite intricacies of divine creation. The serene austerity of a Palladian villa speaks of balance, proportion, and the human longing to impose order upon chaos. Such forms summon the spirit upward, whispering, Here is what you were made for—this symmetry, this splendor, this communion with the infinite.

But beauty is not confined to art or nature. It manifests in fleeting acts of sublimity: a firefighter running into the flames, the quiet heroism of a mother sacrificing for her children, the forgiveness that turns enmity into reconciliation. These moments of moral beauty, though intangible, reveal a deeper reality: that true beauty is inseparable from goodness and truth. The beautiful act, the beautiful soul, and the beautiful world are, in their essence, radiant reflections of a single source.

Classical education, in its essence, seeks to cultivate this love of beauty. It trains the imagination to discern the eternal in the temporal, the transcendent in the fleeting. It teaches students to see not only with their eyes but with their hearts, to behold beauty in Euclidean geometry, Homeric verse, and the natural wonders that inspire both awe and humility. For to love the beautiful is to yearn for the infinite—to stand on the edge of eternity and, like Moses on Sinai, glimpse a glory that no words can fully convey. Beauty, then, does not merely save the world; it reveals the world as it was always meant to be.

Michael S. Rose is author of the New York Times bestseller Goodbye, Goodmen (Regnery), Ugly As Sin (Sophia Institute), The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Benedict XVI: The Man Who Was Ratzinger (Spence), and other books.