Carter's Education Legacy: The Birth of Bureaucratic Mediocrity

The Department of Education, ostensibly dedicated to fostering learning, has succeeded only in institutionalizing ignorance, transforming the nation’s schools into factories of mediocrity.

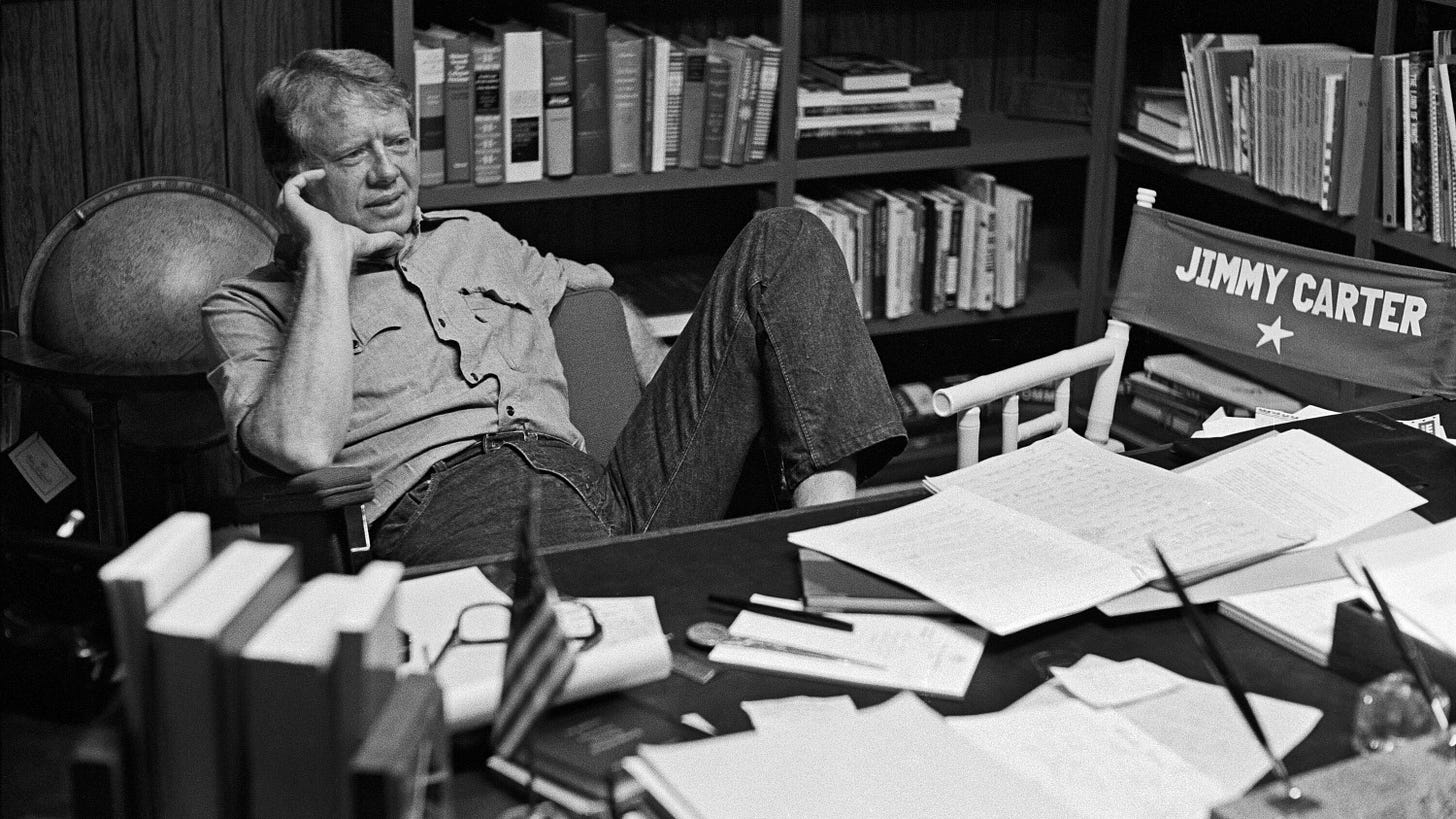

In the sprawling ledger of America’s postwar missteps, the establishment of the Department of Education in 1979 stands as a singularly misguided act of bureaucratic overreach—a monument to well-meaning folly now cast in sharper relief by the passing of its architect, President Jimmy Carter, who died this weekend at the age of 100.

Conceived during an administration often synonymous with malaise elevated to a kind of national mood lighting, the Department emerged as a federal colossus, ostensibly designed to manage the nation’s educational system with promises of equity, excellence, and upward mobility. Yet, much like Carter’s earnest but quixotic attempt to battle inflation, this ambitious endeavor unleashed consequences so vast and labyrinthine they now seem less like policy failures and more like orchestrated effort to champion mediocrity and institutional torpor.

The Department of Education was not born of necessity but of political calculation. Carter, seeking to curry favor with the National Education Association (NEA)—then as now a juggernaut of self-preservation masquerading as reform—promised to elevate education from a nebulous mélange of state and local authority to the gilded heights of federal oversight. What better way to demonstrate the government’s benevolence than by appointing itself the supreme arbiter of learning? Yet from the moment of its inception, the Department seemed less interested in fostering academic excellence than in consolidating power, entrenching bureaucracy, and unleashing a torrent of regulations that would drown local ingenuity beneath a rising tide of federally mandated mediocrity.

Before the Department’s creation, America’s education system, though uneven, was largely decentralized, allowing states and municipalities the freedom to tailor curricula to their unique cultural and economic contexts. This patchwork system produced both its fair share of innovators and laggards, yet it also allowed for experimentation and adaptability. Enter the federal leviathan: with its standardized benchmarks, homogenized curricula, and endless audits, it transformed classrooms from dynamic forums of discovery into sterile assembly lines where rote memorization replaced critical thinking and test scores were exalted as the sole measure of success.

By the early 1980’s, the first grim fruits of this bureaucratic encroachment were already visible. The National Commission on Excellence in Education’s landmark report, A Nation at Risk (1983), read like a eulogy for American schools. It warned of “a rising tide of mediocrity” that threatened to erode not just the nation’s educational foundations but its very future as a global power. “If an unfriendly foreign power had attempted to impose on America the mediocre educational performance that exists today,” the report lamented, “we might well have viewed it as an act of war.” Yet, as historians have since noted, the enemy was not foreign but domestic, and it carried the benign-seeming banner of federal oversight.

One of the most glaring failures of the Department of Education has been its fixation on equality of outcome rather than equality of opportunity. In pursuit of the former, it imposed a litany of mandates that prioritized statistical parity over genuine learning. These well-meaning initiatives—such as the ill-fated No Child Left Behind Act of the early 2000s, itself an ideological descendent of Carter’s vision—tied school funding to standardized test performance, incentivizing a culture of “teaching to the test” that eviscerated intellectual curiosity. Subjects like art, music, and history were relegated to the margins, sacrificed at the altar of STEM worship, while schools in economically disadvantaged areas—those most in need of innovation—were punished for failing to meet unattainable benchmarks.

Meanwhile, the international comparisons grew grimmer by the decade. By the early 1990s, American students ranked embarrassingly low in math and science compared to their peers in Japan, Germany, and even erstwhile Cold War adversary Russia. By the 2010s, the situation had deteriorated further, with the United States languishing outside the top 20 in global rankings for reading, mathematics, and science.

Carter’s bureaucratic brainchild also succeeded in creating a vast and unaccountable administrative apparatus whose primary function appears to be its own perpetuation. Between 1980 and 2020, the Department’s budget ballooned from $14 billion to over $70 billion (adjusted for inflation), yet this tidal wave of funding has done little to improve outcomes. Instead, it has fueled an explosion of middle management—consultants, auditors, compliance officers—whose salaries drain resources away from classrooms and into the ever-expanding maw of federal bureaucracy.

And then there is the ideological creep. By centralizing education policy, the Department has unwittingly (or perhaps deliberately) transformed schools into battlegrounds for the culture wars. From the controversies over Common Core to debates about critical race theory, the federalization of education has ensured that curricula are no longer shaped by communities but dictated by faceless apparatchiks in Washington, whose priorities often reflect the political winds of the moment rather than the needs of students.

In hindsight, the creation of the Department of Education stands as a cautionary tale of what happens when good intentions collide with the immutable laws of unintended consequences. Carter’s experiment in federal oversight has left America with an education system that is more uniform but less effective, more expensive but less innovative, and more centralized but less accountable. The ultimate irony is that a department ostensibly dedicated to fostering learning has succeeded only in institutionalizing ignorance, transforming the nation’s schools into factories of mediocrity.

Michael S. Rose is author of the New York Times bestseller Goodbye, Goodmen (Regnery), Ugly As Sin (Sophia Institute), The Art of Being Human (Angelico), Benedict XVI: The Man Who Was Ratzinger (Spence), and other books.