Beauty Elevates. Beauty Educates. Beauty Endures.

In abandoning beauty, schools do not simply neglect an optional component of education; they amputate an entire mode of knowing.

Step into the institutional fluorescence of any contemporary American school and witness the grim choreography of instrumental rationality: pedagogical technicians murmuring about performance benchmarks, data-driven instruction sheets tacked like catechisms to cinderblock walls, and banners shouting STEM-STEM-STEM like some technocratic war chant.

What you won’t hear is the contrapuntal rise of song, the whisper of charcoal on paper, or the deliberate iambic footfall of memorized verse. These have been excised, like vestigial organs, from the curriculum’s gleaming anatomy. Alack, beauty has been exiled to the broom closet, and its exile, though done in the name of efficiency, is a metaphysical defenestration of astonishing consequence.

This isn’t merely about budgets or shifting pedagogical fads; it’s the epistemic violence of a civilization at war with its own soul. In abandoning beauty, schools do not simply neglect an optional component of education; they amputate an entire mode of knowing. Aesthetic formation is replaced by algorithmic competency. Students move through a world parsed into frictionless fragments, scanning the surface for utility but never lingering long enough to discover meaning. The cost? A generation hyperliterate in manipulation, illiterate in awe.

This is not the education of a human being but of a mechanism: a Homo economicus equipped with the diagnostic tools of an engineer but none of the faculties of a poet. These children grow up mastering systems while never learning to inhabit a moment. Their thinking is a kind of managerial trance—predict, control, output, repeat. The ancient triad of truth, goodness, and beauty has been dismembered, and only the autopsy report remains.

But the classical tradition remembers. Its memory is long, mnemonic, liturgical. The medieval trivium and quadrivium encoded a metaphysical grammar, wherein music was not a leisure activity but an audible map of the cosmos. Geometry was not merely spatial reasoning; it was the contemplative deciphering of order inscribed into reality. One did not simply learn the golden ratio. One saw it—in a Gothic arch, a nautilus shell, or a Raphael Madonna.

In that tradition, beauty was a form of cognition, not decorative ephemera. Manuscripts didn’t merely transmit ideas; their illuminated margins participated in the content. Chant did not accompany doctrine; it was doctrine, sonically embodied. Students learned logic beneath coffered ceilings that echoed Plato’s forms. To learn was to undergo aesthetic initiation.

Recovering this vision means more than tacking on an art elective or mandating quarterly choir performances. It demands re-sacralizing beauty as a necessary organ of knowledge, a sensory sacrament of transcendence

Recovering this vision means more than tacking on an art elective or mandating quarterly choir performances. It demands re-sacralizing beauty as a necessary organ of knowledge, a sensory sacrament of transcendence. Classical schools must reposition the arts not as curricular accessories but as architectural girders, load-bearing columns of the intellectual edifice.

The ancients understood: the Parthenon wasn’t simply beautiful; it was an argument in Doric marble. Its columns ratioed to phi, the golden fingerprint of cosmic order. The rose window at Chartres did not decorate; it catechized, its geometry a theological crystallization in stained light. The Iliad wasn’t entertainment; it was ontological formation, a rhythm of hexameters that beat virtue into the soul.

Art is the vehicle of memory, ethics, and ontology. When Greek boys learned Homer, they not only studied a text, but they also inhabited a rhythm, a cosmology. When medieval peasants knelt beneath Chartres’ kaleidoscope, they didn’t merely admire—they ascended. Through aesthetic encounter, they perceived what Aquinas would call the species intelligibilis of truth.

What we now call the fine arts functioned as epistemological ligaments, binding perception to cognition, body to intellect. To remove them is not to streamline education; it is to sever the corpus callosum of the curriculum. The result is educational aphasia: students can parse, tabulate, perform—but not see. The transcendent vanishes into the crawlspace of curricular irrelevance.

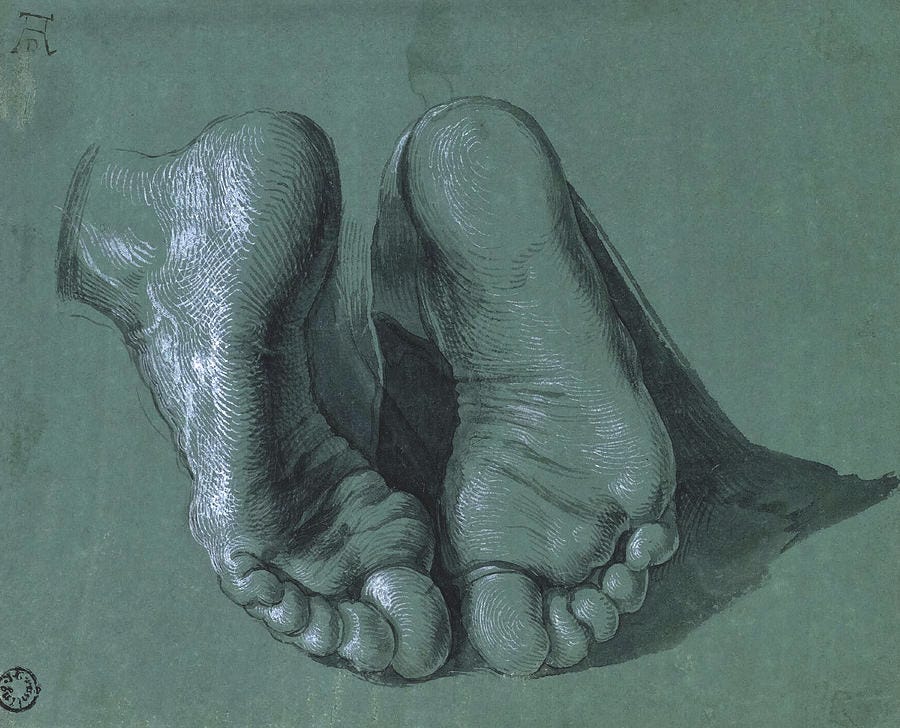

Consider the visual arts. In a classical program, drawing becomes a moral exercise in attention. A still life is not simply an object to replicate; it is a confession of created order. In sketching the human hand, the student rehearses the Imago Dei. To copy a manuscript is not to mimic but to commune across time with the anonymous scribes of tradition. The eye becomes a contemplative organ, not merely a sensor of stimuli.

In music, students experience harmony as metaphysics incarnate. Chant calibrates the soul to liturgical time. Polyphony trains the ear to dwell in tension without dissolution. To sing in parts is to live communally in sound. Advanced students encounter fugue as theological architecture: Bach as a mathematician of the sacred. They do not merely play music; they traverse the architecture of heaven.

Drama, too, is transfigured. In memorizing and performing verse, the student does not merely interpret text—he embodies logos. A Shakespearean monologue becomes moral vivisection. Portia’s plea for mercy is not an assignment; it is jurisprudence enacted. Antigone is no longer literature; she is a lived dialectic in flesh and breath.

The aesthetic disciplines do not stand apart from other studies but breathe through them. Geometry explains cathedral windows. History finds voice in folk song. Theology sings in Palestrina and shouts in Bernini. The arts do not supplement knowledge; they transubstantiate it.

Integration is not pedagogical frill—it is intellectual integrity. When students design Roman villas while reading Vitruvius and solving for load-bearing angles, they incarnate thought. When they sing spirituals while reading Douglass, they hear the soul of a people, not just the facts of oppression. When they illuminate Dante while diagramming his cosmology, they descend into the inferno and rise through the spheres.

To re-center beauty is to reassert the grammar of creation. It is to insist that to know is to see truly, that the world is not data to be mined but mystery to be sung. Beauty renders knowledge radiant. It unveils.

Thus, the restoration of the fine arts is not remedial—it is revolutionary. It produces not just scholars but souls. It trains not simply intellects but imaginations. It recovers the contemplative in the age of the algorithm.

To build a school around beauty is to raise up students who do not merely graduate but ascend.

And that is worth singing about.

Michael S. Rose, a leader in the classical education movement, is author of The Art of Being Human, Ugly As Sin and other books. His articles have appeared in dozens of publications including The Wall Street Journal, Epoch Times, New York Newsday, National Review, and The Dallas Morning News.

Thank you.

Trained as an arts instructor (music) I have long contended that the arts are the glue for the curriculum, that without the arts we don’t have wisdom. Unfortunately, few of us are trained to see it or use it that way, even us arts instructors. I premise that every Classical instructor for every grade and subject should be required to have some minimal skill and experience across the arts and demonstrate depth in at least one.